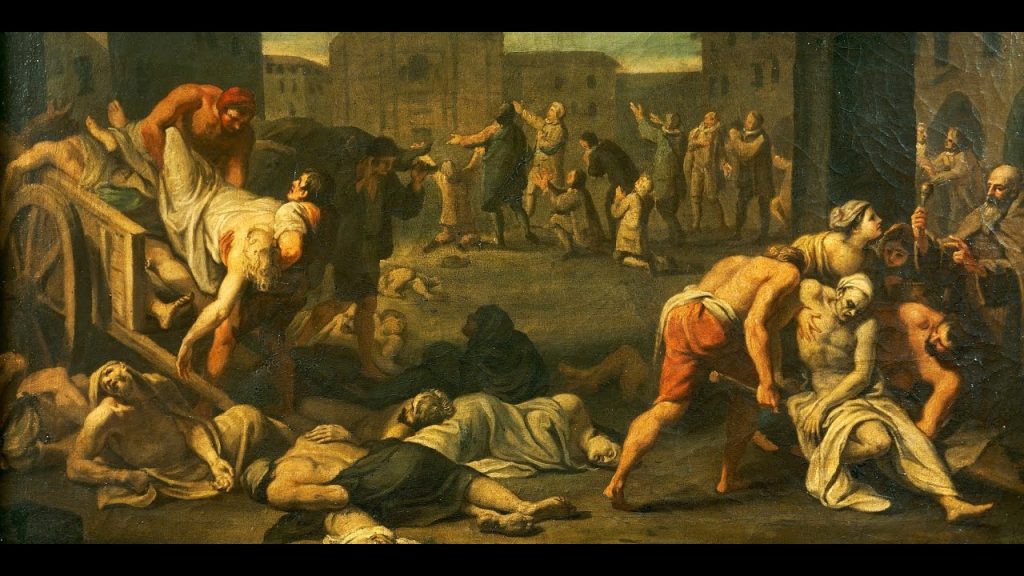

Despite the apparently universal human need to look back to a golden age of long summers, full churches, and ecumenical unanimity, the reality of human history is replete with examples of chaos and catastrophe in every age. There has never been a century, or even a decade, when there have not been devastating storms, calamitous earthquakes and overwhelming floods and tsunamis. These have been a regular feature of all human societies whether Christian or non-Christian, orthodox or heretic, and have therefore demanded an attempt at theological explanation from the Churches long before this present age.

As an Orthodox Christian, a western convert member of the ancient Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate, it is almost impossible to consider reflecting on the use of the Bible in making sense of the human experience of chaos and catastrophe without making reference to the theological considerations of Orthodox writers of the past. Indeed for Orthodox Christians, as undoubtedly for many others, there is a communion in time with these fathers of the past, who are present with us through their writings and through their present and living communion in Christ. Therefore their opinions count. They are not simply a useful quarry for proof texts, but they have something to add to our own thinking. They are always contemporary if we allow them to be, and if we take care to comprehend the universal implications of their historically contexualised thought.

The Orthodox theologians of the past had to ask the same questions which natural disasters force upon our own theological and spiritual consciousness. Their experience of earthquakes, storm, floods and plague are not so dissimilar to ours. They heard of terrible events in far off places, as many of us do. Or they experienced them for themselves in all of their frightening power. We cannot ignore their reflections on such events if we wish to be rounded in our own reflection.

These theological, spiritual, historical and political considerations can be found in a variety of sources. The most comprehensive are the histories and chronicles which Christian authors compiled. Since these are attempts to document events over a period of years and even centuries they contain many references to natural and social disasters of various kinds. These events will also be found recorded and interpreted in sermons and letters, in lives of the saints, in theological treatises, and in the interesting category of writings which record visions and prophecies.

The study of the documentary materials of even the first five or six centuries of the Church would provide an important contribution to our present study of the Christian reponse to catastrophe, and especially the use of the Bible in developing such a reponse. But for the purposes of this short paper only one early document will be considered. This is the Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite[1], composed in about 507 AD, and therefore in a controversial period of Church history as the Chalcedonian and Non-Chalcedonian parties in the Church were drawing apart.

Joshua’s Chronicle covers the years between 494-506 AD in some detail, and during this relatively brief period there are a number of natural and social catastrophes. The title of the text is in fact given as ‘A History of the time of the affliction at Edessa and Amida and throughout Mesopotamia’.[2] It is likely that Joshua was not in fact the author[3], rather a later scribe, but the original author is clearly local and contemporary to the events which are described. He introduces his account by addressing it to the Abbot Sergius, who had requested that he write about,

“..the time when the locusts came, and when the sun was darkened, and when there was earthquake and famine and pestilence”.[4]

Almost immediately we receive a summary of the interpretation which the author seems to wish to place on these recent events. He says,

“..you wish to leave in writing memorials of the chastisements which have been wrought in our times because of our sins, so that, when they read and see the things that have happened to us, they may take warning by our sins and be delivered from our punishments.”[5]

Let us have this initial impression in mind, while we consider what were the disastrous events of those times which had induced the unknown chronicler, let us call him Pseudo-Joshua, to take up his pen. These events may be characterised as natural or political. On the one hand there was a plague of boils which became more harmful to the population over the years 496-497 AD. At first it caused irritation and revulsion, but left nothing more lasting than scarring on the affected limbs, but later it intensified and caused blindness in those afflicted.

Then in 497 AD there was an earth tremor which caused some of the civil buildings in Edessa to collapse with a loss of life. In the following year there was another earth tremor which destroyed church buildings in several places with the loss of life of those who had run to them for shelter. In 499 AD a plague of locusts descended on the region, and consumed everything for hundreds of miles around. This provoked a desperate famine which caused mass starvation. Indeed the situation throughout the region described in the chronicle remained critical until 501 AD when it seems that there was the beginning of a recovery in agricultural production.

The political catastrophes were rooted in the long-standing conflict and tension between the Roman and Persian empires. This was a border region and often suffered from being a contested area. In 502 AD open warfare flared up again and the citizens of Edessa, Amid and the surrounding towns and villages, having just recovered from a natural disaster, found themselves caught between the pressures of supporting their own Imperial troops and their allies, and suffering the predations of the Persians.

In just a few years Pseudo-Joshua and his contemporaries had experienced as devastating a series of catastrophes as any suffered in our own times, with many tens of thousands left dead as a result of disease, starvation and war.

This is the context in which he is able to reflect on his own experiences, and develop a theological understanding of the terrible events which had recently taken place. He is writing from a first-hand contemporary point of view, and therefore, whether or not his understanding is appreciated or rejected in our own times, it must be allowed to speak for itself as an authentic, Orthodox consideration. Certainly not the only Orthodox voice, other voices will require further research and study, but a voice of experience nonetheless, rooted in the Orthodox tradition.

Returning to Pseudo-Joshua’s opening opinion. He speaks of sins and chastisement, warnings and punishments. It would be simplistic to assert that he is assuming that all natural and political catastrophes are a direct punishment for particular sins committed. Nevertheless he is clear that there is a connection between sin and chastisement.

A few examples from the chronicle will show that there is a firm connection between the two in Pseudo-Joshua’s thinking.

“For who is able to tell fittingly concerning those things which God has wrought in His wisdom to wipe out sins and to chastise offences?”[6]

and

“…these chastisements … were sent upon us for our sins”[7]

Now this way of thinking is not alien to the Scriptures. Indeed the author of the Book of Hebrews writes,

“For whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth, and scourgeth every son whom he receiveth.” Hebrews 12:6

It would seem that Pseudo-Joshua wishes to place his theological reflection on the disasters of his time within exactly such a framework of chastisement. It should be noted that he is writing to an Abbot, and is describing the situation within an essentially Christian civil community. Therefore he is writing about the relationship between the Christian God, the Christian community, and the historical, chaotic and catastrophic context in which that relationship takes place.

This is made explicit when he quotes from the parable of the tares and wheat. The tares or weeds have been sown by an enemy among the seeds of wheat which the farmer has planted. This is not a parable about those who have no knowledge or faith in the Christian God. If that were so then we would read of wheat being sown among weeds. Therefore Pseudo-Joshua has his own Christian civil society particularly in mind as he writes.

Indeed he has in mind very particular sins of his community which he believes have brought about this well deserved chastisement.

He describes this cause and effect at the beginning of his detailed annual chronicles, as though wishing to make it abundantly clear that the ultimate cause of all of the disasters was spiritual. He says,

“At this time our bodies were perfectly sound all over, but the pains and diseases of our souls were many. But God, who finds pleasure in sinners when they repent of their sins and live, made our bodies as it were a mirror for us, and filled our whole bodies with sores, that by means of our exterior He might show us what our interior was like unto, and that, by means of the scars of our bodies, we might learn how hideous were the scars of our souls. And as all the people had sinned, all of them were smitten with this plague”[8].

We must remember that Pseudo-Joshua is sharing in this experience. He is not writing at a great distance of miles or time. Edessa was a famous Christian city, and considered itself especially protected and blessed by God, and yet our author suggests that under the surface there was a spiritual corruption and sickness.

He illustrates this by referring the immediate justification for this chastisement of God to the enthusiastic celebration of pagan rites and luxurious living. In particular during a festival in May of 495 AD, much of the population seems to have participated in such a celebration, lighting the streets in honour of a dancer, Trimerius, who performed in the displays which the legal code of Theodosius had allowed only if they were decent. It would seem that in Edessa at this time they were still a scandal to Orthodox Christians. Not only were members of the population supporting such un-Christian theatrics, but they were failing to give thanks to God for the material prosperity which their city enjoyed.

In fact the plague of boils failed to bring the city to repentance. Indeed we are told that both the rich and poor gave themselves to sin. Slandering one another, having regard to people’s position, adultery and other sexual immorality. The consequence, as far as Pseudo-Joshua is concerned, was that the Christian community found it more and more easy to give way to sin.

In terms that are perhaps reminiscent of the experience of Christians communities in all ages, he describes how,

“..they neglected also to go to prayer, and not one of them gave a thought to his duty, but in their pride they mocked at the modesty of their fathers, who, they said, did not know how to do things as we do”[9].

This same connection between sin and chastisement is evident in the account of the first appearing of the swarm of locusts. On this occasion they were seen to lay eggs but were not so numerous as to cause major problems. Yet their appearing is described as,

“A proof of God’s justice…for the correction of our evil conduct”.[10]

What is interesting is that Pseudo-Joshua tends always to understand the experience of the Christian community, however catastrophic, as being an opportunity for repentance and a chastisement, rather than a punishment. The term chastisement appears again and again, whereas the word punishment appears rarely and almost always in the context of God acting against the enemies of his people. An example can be found when the depredations and aggression of the Persian king are described,

“But we place our trust in the justice of God, that He will bring upon him a greater punishment”.[11]

There is a great difference between chastisement and punishment, and on most of the occasions where Pseudo-Joshua refers to chastisement he also indicates that it has a positive element, in distinction to punishment. He quotes the words of St. Paul from 1 Corinthians,

“When we are judged, we are chastened of the Lord, that we should not be condemned with the world”[12].

This is one positive aspect he draws from all of the difficult circumstances he has witnessed. To be chastened is to be the object of God’s care. It is those whom He loves that He chastens. Over and over again, just as he links chastening with sin, so he also links chastening to hope for the future.

“The whole object of men being chastened in this world is that they may be restrained from their sins, and that the judgement of the world to come may be made light for them”[13].

To experience hardship, even catastrophe, is therefore a spiritual opportunity. This certainly does not mean that anyone outside any particular circumstances should take it upon themselves to judge others. We cannot say that these other people have sinned simply because they experience some catastrophe, and Pseudo-Joshua does not seem to want to use the Scriptures to suggest that is the case. But he does want to recognise the sin in his own community and believes the various disasters, signs and warnings are all means by which God was calling the Christian people of Edessa to repentance.

He understands this chastening in a positive manner by considering that,

“Had not the protection of God embraced the whole world so that it should not be dissolved, the lives of all mankind would probably have perished”.[14]

Is this not rather a difficult measure by which to see the hand of God? That though things were bad they could have been worse? Certainly a secular perspective might indeed take such a view. But the Christian faith demands that we consider the corruption of sin and the judgement due to us all as sinners. The ‘wages of sin are death’. This is certainly not viewed by Orthodox Christians as meaning that there is an eternal punishment which God will mete out to all who do not know Him. But it is rather understood that apart from life in God there is a falling apart of our world and of ourselves. Therefore it is indeed to be understood positively that God does not allow this to happen as we deserve, but does show mercy to His creation – even as it groans and travails awaiting a rebirth into the age to come.

Pseudo-Joshua seems to be asking all those who experience chaos and catastrophe how they will respond to it. There could be anger which considers all such hardships as unwarranted – but he reminds his readers that all Christians are deserving of chastisement for sins. There could be despair – but he reminds his readers that these sufferings can be a means of repentance and life.

But it would appear that this must be an internal and spiritual judgement based on the reflection of those who are in the midst of chaos. No one should say that some others are the particular object of God’s wrath, rather all those who read or hear about a disaster elsewhere should consider their own spiritual state. We should ask ourselves whether, if such events indeed might be a chastening of God’s people, we are not worthy less of chastening and rather of punishment.

Pseudo-Joshua make this same point. He considers all of the events in the surrounding cities, and has to declare that,

“Not a man of us was restrained from his evil ways, so that our country and our city had no excuse”.[15]

Therefore it is clear that the main use which a Christian should make of chaos and catastrophe is to be turned to a personal repentance. Both in those who experience such catastrophes, which according to Pseudo-Joshua should be considered as a chastisement, and also in those who hear about such catastrophes but are spared the experience of them.

Now it would seem rather monstrous if that was all of the theological reflection which Pseudo-Joshua offers. We know, as Christians, that all people, as sinners, deserve the wrath of God, but we are also deeply aware that God has become part of His own creation and that He shares in the pain and distress of all those who suffer. It is rather a mystery, in the sense of something beyond simple human explanation, how we are to hold together the love of God and the sense that chaos and catastrophe might be something positive in His will for us.

When someone has a car accident and walks away with a minor injury we might easily understand that they have been given a wake up call and are being called to look at the substance of their lives. But when hundreds of thousands of people are swept away in a tsunami it is impossible to speak. What can be said. How is this part of a Divine plan.

Pseudo-Joshua also appreciates this need for silence, and he says,

“Who is able to tell fittingly concerning those things which God has wrought in His wisdom to wipe out sins and to chastise offences? For the exact nature of God’s government is hidden even from the angels”[16].

This must give us cause to be very hesitant in how we speak about disaster. We hold the theological certainties that we deserve judgement, that we are loved by God, that He will do all that He can to bring us to repentance and to union with Himself as far as our freewill allows and that this includes what Pseudo-Joshua and indeed St. Paul call a chastening. But beyond that – who is able fittingly to tell.

Indeed several times Pseudo-Joshua indicates that the events which came across the people of the region are not to be understood as directly caused by God, as though God directly caused an earthquake for instance. When speaking of the tribulation caused by the predations of the Persians he says,

“Now I do not wish to deny the free will of the Persians, when I say that God smote us by their hands; nor do I, after God, bring forward any blame of their wickedness; but reflecting that, because of our sins, He has not inflicted any punishment on them, I have set it down that He smote us by their hands”[17].

It seems that we must keep in mind both the direct action of the Persians and their own liability for their barbarity towards the Romans in Edessa and elsewhere, while also understanding that there is a permissive will of God which allowed the Persians to act, but which does not allow us to ascribe the catastrophe directly to God. Likewise it might be proposed that natural disasters are allowed by God, and used by God, but need not, perhaps even should not, be understood as being directly caused by God.

In our own experience if we have a young child who runs away from us and falls, scraping her knee, then we might use the experience to warn the child that this is what happens when she runs away from her parents. But this would not mean that we had caused the injury, rather that in allowing a certain necessary freedom we made it possible that such an injury could happen.

Bearing in mind the fact that Pseudo-Joshua links the various catastrophes which the Christian people of Edessa suffered very closely to their sinfulness, it is surprising that there is never any sense of triumphalism. He is never pleased that these things have come upon them, and he always unites himself with them. He says that ‘not a man of us’ was restrained from sin, he does not say that ‘not a man of them’. And when he records the suffering of Edessa and Amida he writes ‘sadly’ and in ‘melancholy tales’, and with ‘words of grief and sorrow’. There is no need for a belief that in some sense disasters come as a means of chastisement to be devoid of a genuine emotional commitment to those who suffer. Pseudo-Joshua insists throughout on the need for repentance among those who are in these circumstances. As far as he is concerned the only positive route through them is a closer relationship with God. But he weeps with them, and prays with them, and hungers with them because he is one of them.

But there is also a sense that not all those caught up in such natural disasters are equally the subjects of God’s chastisement. While he often describes the city folk as sinful, when it comes to the village people who flock to the city during the famine he considers them a different case. He quotes the psalms of David saying,

“If I have sinned and have done perversely, wherein have these innocent sheep sinned?”[18].

Clearly we may also consider that there are those caught up in catastrophe who are not the objects of chastisement, though all may use such events in a positive manner. The author addresses these people directly when he says,

“As for those who are chastised because of sinners, whilst they themselves have not sinned, a double reward shall be added unto them”[19].

This passage can be taken in several ways. Both that there are those who suffer due to the direct actions of those who are sinners, and also that there are those who suffer – as the poor in Edessa – because of the chastisement which others deserve. Yet in both cases there is the scope for a positive outcome within a Christian worldview, and not necessarily in a purely material sense. If the martyr is a Christian hero then we cannot always expect material circumstances to be the measure of the ‘double reward’.

But as with the perception of chastisment and the call to repentance, this understanding of being an innocent participant is also perhaps best left to those who are in the midst of particular circumstances. If it is not our place to judge others, then we should hesitate to judge entirely, for good or bad, but as those outside such circumstances we should perhaps treat all alike, while also drawing the lessons of repentance for our own lives.

There are yet more lessons which Pseudo-Joshua offers us. The people of Edessa, though the judgement which came upon them is considered entirely justified by him, are nevertheless shown to grow in this circumstance. Their own response to those in need among them shows us how we might act towards those in such situations.

It has been suggested that according to Pseudo-Joshua chaos and catastrophe calls us to examine our own lives, whether we are caught up in such events or not. It has also been suggested that we might recognise that some are caught up in such situations through their own actions, and others are innocently swept up due to the actions of others.

The Chronicle also shows how we should act towards those in such situations. Pseudo-Joshua is quick to condemn his own Christian city as having lost something of their love for God, but he also commends them as they grow in the practice and experience of such love in the midst of disaster. He describes in some detail the suffering in the city during the great famine, and how many people were starving and dying each day. Yet there is no record of anyone ever reproaching those who were in such despair. Looking back to the events after they had passed Pseudo-Joshua is clear that they were all to be used as a means of bringing folk to repentance, but while in the midst of them there is no evidence that any of the Christian leaders made particular Christians responsible for the events which had overtaken them. No one is to be found saying that the people of Edessa and Amida should not be helped because God was punishing them.

On the contrary it seems that from all sides there was a growing desire to be of service to those in need. A short description of some of the means by which aid was provided, and by which care and respect was shown to those in these circumstances will show the response to chaos and catastrophe which Pseudo-Joshua expects from other Christians. In the first place the Emperor provided ‘no small sum of money to be distributed to the poor’[20].

Mar Nonnus, the cleric who had the care of hospitality, organised the Christian brethren under his charge to collect the bodies of all those who had died each day. The people would gather at the gate of the ‘Hospital’ and would help to bury the bodies. The stewards of the Churches established an infirmary for those who were most ill, and if people died there, and many did, then their bodies were also taken with respect and buried.

The Governor converted the porches of the public baths into places where the poor who had come into the city from the villages could sleep, and he provided straw and mats for them to sleep on. These examples encouraged the wealthy in the city to establish infirmaries of their own in their own properties, and many of the poor found shelter there. Even the soldiers of the Roman garrison provided places for the sick to sleep and fed them as best they could at their own expense.

Over a hundred people a day were dying in the city, and the poor from the countryside were even dying on the roads approaching the city.

It would seem that Pseudo-Joshua wishes us to note the change in character within the Christian community. Where there was once a self-centered and indulgent way of life, now there was a concern for others and a re-orientation of spiritual life on God. Indeed he notes that during the famine the people of the city gathered for public prayers asking that the strangers in the city might be spared its depredations. The Christian community prayed,

“If I have sinned and done perversely, wherein have these innocent sheep sinned?”

At this point in his chronicle Pseudo-Joshua records that the time of the pagan festivities which he believed had provoked the chastisement of the city came around. But in this year, 501 AD, the emperor forbade that it be celebrated in any place in the empire, and the lewd dancers were not allowed to dance. Within thirty days of its abolishing the price of food had dropped and sustenance came in the necessary quantities to those in and around the city.

It is clear that Pseudo-Joshua links the removal of that which God might have found offensive in a Christian city to the end of the chastisement which the city needed for its reformation. Yet he notes that the reformation was hardly a voluntary one, and was rather the result of the emperor than the civic authorities of Edessa. But Pseudo-Joshua adds that,

“God, because of the multitude of His goodness, was seeking an occasion to show mercy even unto those who were not worthy”[21].

Of course the objectionable celebrations were a symptom of the spiritual malaise in the city, and were not the only, or even the most important locus of sinful activity. And it is telling that Pseudo-Joshua indicates that he does not wish to enumerate all the sins of the chiefs of the city. Though he includes all of the people of the city in his criticism of their past activity, nevertheless he seems to judge the leaders of the city more strictly, while judging the poor and the strangers as innocent.

It is clear that Pseudo-Joshua cannot be used to support the simplistic view that people sin and so deserve to be punished. He addresses himself especially to a criticism of his own Christian community in Edessa. In that context he uses the Scripture to link the behaviour of the community to a chastising of God. Yet even though this painful experience is considered by him as justified, nevertheless it is to be understood in a positive sense as exhibiting the goodness and love of God within the catastrophic events. This can only be recognised through careful and spiritual reflection and is not to be imposed as an external interpretation on the events which others find themselves overwhelmed by.

On the contrary these events are an opportunity for the Christian community to rouse itself to help those in need, and especially to consider that the poor and the strangers among them are the least liable to any condemnation. He commends those who care for these needy in practical ways, and this is one of the means by which the Christian community works out its reflection and repentance in the midst of such events.

The Scriptures are consistently used by Pseudo-Joshua in a positive sense, even when he is suggesting that chaos and catastrophe are a means of God chastening His own people. God chastens those whom He loves, and chastening is a positive training for life and not a punishment unto death.

In the end, faced with chaos and catastrophe, if we follow the theological reflection of Pseudo-Joshua, we must be content to ask ourselves how we should respond. We cannot respond for other people, and especially we cannot condemn other people. It is a blessing if we are brought to repentance by a consideration of the situation in which others find themselves, brought to reflection on all the blessings which we have already received and enjoy. But it is not a true repentance at all if we are not moved beyond spiritual thoughts into positive actions to help those who find themselves caught in such situations.

Of course this is only one author from the sixth century. There are

other witnesses of these same events, and witnesses to the position of the

Eastern Church over many centuries. Further study will provide much more

material to be included in any contemporary reflection on the issues of the use

of Scripture in regard to Chaos and Catastrophe. Yet this is perhaps a small

contribution.

[1] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882.

[2] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.1

[3] Tombley, Frank and Watt, John trans. The Chronicle of Pseudo-Joshua the Stylite. Liverpool University Press. 2000. p.xxiv

[4] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.1

[5] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.2

[6] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.3

[7] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.3

[8] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.17

[9] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.21

[10] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.23

[11] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.14

[12] 1 Corinthians 11:32

[13] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.4

[14] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.3

[15] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.26

[16] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.3

[17] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.5

[18] 2 Samuel 24:17

[19] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.5

[20] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.31

[21] Wright, William trans. The Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite. Cambridge University Press. 1882. p.35