In the 21st Century, the Coptic Orthodox Church, and other Orthodox Churches, are part of the Christian landscape, and have a full and active part to play in the life of our nation. It is no longer only a pleasant surprise to see an Orthodox bishop being interviewed by the national media, indeed one of our own Coptic Orthodox bishops. But it has become rather a regular occurrence whenever there is some important national event, or international crisis requiring a comment. Increasingly members of the Orthodox Churches in the UK are British, either local British converts, or the children and grandchildren of those Orthodox Christians who came to the UK 30, 40 or 50 years ago.

As just such a British convert to the Orthodox Church, within the Coptic Orthodox community in the UK, and serving as a priest of the Diocese of the Midlands of the Coptic Orthodox Church, I am often asked why I became a member of a foreign and alien Church. But in fact the Coptic Orthodox Church has a shared history with the British Isles, and the earliest Christian experience here was in unity with the Church in Egypt, and shared the same Apostolic teaching, and many of the same spiritual practices, though often in a local form.

Of course it would be a mistake to imagine that there are significant direct links between the British Isles and Egypt. There are none, and it is not the case that any Egyptians evangelised these islands. Most of the connections are indirect. St John Cassian, for instance, brought a knowledge of Egyptian monasticism to southern France, and it found its way to the north and especially to to Ireland, not least by means of the Irish themselves, who travelled across Western Europe, and could be found in the monastery of Lerins in the Mediterranean. This monastery had been founded with a definite Egyptian influence, and St John Cassian, a monastic writer who had visited the Fathers of the Egyptian Desert, and had written down his spiritual conversations with them, and a description of their way of life, established a monastery and convent only a little way around the coast.

St Patrick, the great Apostle of Ireland, was one of those who spent some time in the monastery of Lerins before he set off to evangelise Ireland. He would certainly have come under the influence of Egyptian Desert monasticism at this time, and the writings of St John Cassian were popular in Ireland in later years. Tirechan, a 7th century Irish bishop, believed that he spent up to 7 years at the monastery of Lerins, though a slightly earlier source known to Tirechan, Bishop Ultan, thought that he had been in the monastery as much as 30 years. Certainly his association with the monastery of Lerins, and the influence of St John Cassian in that area, would have provided St Patrick with a knowledge of the Egyptian Desert monastic practice and spirituality.

The writings of St John Cassian about Egyptian monasticism also influenced St Benedict, the great Western monastic Father. Indeed, he advised those who followed his Rule to read and study the writings of St John Cassian. More than that we see the use of the works of St John Cassian when his description of 10 signs of humility as described in the Desert are developed into 12 steps towards humility within Western monasticism. There is a very clear dependence, even though it is developed, in the early Western monastic tradition on the Egyptian Desert tradition.

This can also be seen in the works which are known as the Irish Penitentials. These are guides for those engaged in spiritual direction. These can be found in the 6th and 7th centuries in Wales and Ireland, and even in England. The Penitential of St Theodore of Tarsus, the Syrian Archbishop of Canterbury, has its roots in the same tradition. It is noted that these Penitentials, or guide books for penance, deal with the need for frequent confession to a spiritual father, the eight deadly sins, and healing of sin through the opposite virtue, all of which are found in the writings of St John Cassian as he describes the Egyptian monastic practice and spirituality.

The Life of St Anthony by St Athanasius was also known in the British Isles. We should not forget that St Athanasius had been exiled to Treves in Gaul, which is now Trier in modern Germany, and he was exiled to Western Europe on two occasions. His Life of St Anthony was translated into Latin less than 20 years after he composed it. This is a another means by which the spirit of Egyptian monastic spirituality reached the West, and the British Isles.

It was through these indirect means that the influence of the Coptic Orthodox monastic spirituality was felt in the British Isles. But this does not mean that there were not a few travellers who made their way to Egypt, and a few others who made their way from Egypt. There influence is interesting but not significant in the life of the Church in the British Isles, compared to the monastic influence of the writings of St John Cassian and the Life of St Anthony.

We certainly know that from ancient times trading for tin took place from the Mediterranean to Britain. Indeed the legend that our Lord Jesus visited Britain with his uncle, Joseph of Arimathea, is based on the well established fact that there was trade in tin across the Roman empire. We have a documented example in the life of John the Merciful, the Greek Patriarch of Alexandria in the early seventh century. In the Life we find mentioned a sailor who turned to the Patriarch for help, and who was sent to Britain. This excerpt describes a miracle which took place, and also illustrates the trade connections between Egypt and Britain at this time, and in earlier centuries.

He immediately ordered that one of the ships belonging to the Holy Church of which he was head should be handed over to the captain, a swift sailer laden with twenty thousand bushels of corn. … Then after the twentieth day we caught sight of the islands of Britain, and when we had landed we found a great famine raging there Accordingly when we told the chief man of the town that we were laden with corn, he said, “God has brought you at the right moment. Choose as you wish, either one ‘nomisma’ for each bushel or a return freight of tin”. And we chose half of each.’ … ‘Then we set sail again,’ said the captain, ‘and joyfully made once more for Alexandria, putting in on our way at Pentapolis.’* The captain then took out some of the tin to sell-for he had an old business-friend there who asked for some-and he gave him a bag of about fifty pounds. The latter, wishing to sample it to see if it was of good quality, poured some into a brazier and found that it was silver of the finest quality. … The captain was dumbfounded by his words and replied: ‘Believe me, I thought it was tin! But if He who turned the water into wine has turned my tin into silver in answer to the Patriarch’s prayers, that is nothing strange. However, that you may be satisfied, come down to the ship with me and look at the rest of the mass from which I gave you some.’ So they went and discovered that the tin had been turned into the finest silver.

This is not a much later legend with fanciful embellishment, but the life of John the Merciful was written by a Leontius who was his contemporary, and therefore it is entirely reasonable to conclude that trade between Egypt and  Britain took place and was taking place at this time. There are physical artifacts which indicate that this was the case. Many Anglo-Saxon graves have been found to contain what are known as Coptic bowls. These are metal bowls indicating the very high status of the person buried. Not all of them are from Egypt, but they are from the Eastern Mediterranean and indicate that into the 7th century there was still trade between Britain and the East.

Britain took place and was taking place at this time. There are physical artifacts which indicate that this was the case. Many Anglo-Saxon graves have been found to contain what are known as Coptic bowls. These are metal bowls indicating the very high status of the person buried. Not all of them are from Egypt, but they are from the Eastern Mediterranean and indicate that into the 7th century there was still trade between Britain and the East.

But there are even clearer archaeological materials which show that there was a connection between Egypt and Britain. The great shrine of St Mina was famous outside of Egypt, and pilgrims travelled great distances to pray at his  church, as well as visit the other great Christian sites. We know that some British people travelled to Egypt and prayed at the shrine of St Mina because they brought back the little pottery flasks filled with blessed oil which were sold there. These are found in many places in Europe, but also in the British Isles. We know that the shrine was especially popular between 500-640 AD. But after the Muslim invasion of Egypt international pilgrimage dried up.

church, as well as visit the other great Christian sites. We know that some British people travelled to Egypt and prayed at the shrine of St Mina because they brought back the little pottery flasks filled with blessed oil which were sold there. These are found in many places in Europe, but also in the British Isles. We know that the shrine was especially popular between 500-640 AD. But after the Muslim invasion of Egypt international pilgrimage dried up.

These pilgrim souvenirs have been found in Britain at Canterbury, Faversham, Derby, York, Durham and on the Wirral. Of course this does not prove that pilgrims travelled all the way to Egypt and brought back these flasks, and the others which have been lost over the centuries. But it is reasonable to assume that some did, and certainly it seemed worthwhile to people over an extended period and in different places, to bring or send these flasks to the British Isles.

In fact we do know that there were Western pilgrims who visited the Eastern Mediterranean. The famous pilgrim, Etheria or Egeria, wrote about her pilgrimage which took place in 385 A.D. She climbed Mount Sinai, for instance, and saw Egypt below her in the distance. She visited some of the towns of Egypt and describes them. Egeria is not from Britain, she was probably from Gaul, and of some importance. But where she travelled, it was not impossible for others to follow.

One such is described by St Adomnan or Adamnan, the famous Abbot of the Monastery of Iona. A traveller, the Bishop Arculf, was stranded in the north of Scotland when he was shipwrecked, and he described his recent journey to the Holy Places to Adomnan, who put his notes together with materials from other sources, and produced a volume called – The Holy Places. This journey took place in about 680 A.D.

The Life of St David, the patron of Wales, by Rhygyvarch, of the 11th century, describes him visiting Jerusalem with some companions in the 5th century. He says that he found the details of St David’s life in various ancient manuscripts. Perhaps it was legendary by the 11th century, but certainly it would seem that St David was associated with a journey to the Eastern Mediterranean. Part of the Life says…

At length they arrive at the confines of the desired city, Jerusalem. On the night before their arrival an angel appeared to the Patriarch in a dream, saying, “Three catholic men are coming from the limits of the west, whom you are to receive with joy and the grace of hospitality, and to consecrate for me to the episcopate.” The Patriarch made ready three most honourable seats, and when the saints came into the city he rejoiced with great joy and received them graciously into the seats which had been prepared. After indulging in spiritual conversation, they return thanks to God. Then supported by the divine choice, he promotes holy David to the archepiscopate.

At length they arrive at the confines of the desired city, Jerusalem. On the night before their arrival an angel appeared to the Patriarch in a dream, saying, “Three catholic men are coming from the limits of the west, whom you are to receive with joy and the grace of hospitality, and to consecrate for me to the episcopate.” The Patriarch made ready three most honourable seats, and when the saints came into the city he rejoiced with great joy and received them graciously into the seats which had been prepared. After indulging in spiritual conversation, they return thanks to God. Then supported by the divine choice, he promotes holy David to the archepiscopate.

Yet, there is a portable altar stone preserved in the Cathedral of St David, and said to be that which the Patriarch of Jerusalem gave him to celebrate the Liturgy upon. It may well be that he did indeed visit Jerusalem in the 5th century, one of a number of British pilgrims heading to the East.

Of course it is also necessary to consider those who might have travelled in the other direction. There are a few who step out of the shadows. But their significance should not be overestimated. We know little or nothing about them. It is certain, however, that they did not bring Christianity or monasticism to the British Isles. They were individuals or small companies of monks who found a home here, and were remembered.

In the churchyard at Aghabulloge in Cork, Ireland, there is a pillar with an Ogham inscription. Ogham was a form of monumental inscription made by marks along the edge of a surface and was used in Ireland and parts of the British Isles. This monument is known as St Olan’s Stone and refers to a local Christian who lived here in the 8th century at the latest. According to Samuel Ferguson, in his work on the Ogham inscriptions of Ireland, Wales and Scotland, the text of the monument reads…

In the churchyard at Aghabulloge in Cork, Ireland, there is a pillar with an Ogham inscription. Ogham was a form of monumental inscription made by marks along the edge of a surface and was used in Ireland and parts of the British Isles. This monument is known as St Olan’s Stone and refers to a local Christian who lived here in the 8th century at the latest. According to Samuel Ferguson, in his work on the Ogham inscriptions of Ireland, Wales and Scotland, the text of the monument reads…

Anm Corpimaq fuidd eguptt

This is translated as “Pray for Corpmac the Egyptian”. Some websites have suggested that the inscription says “Pray for Olan the Egyptian”, but this is not the case at all, as the very detailed analysis of the script by Ferguson shows. So who was Corpmac and how was he related to Olan, and where either of them from Egypt? In the first place, Ferguson notes that a great many of the Irish and Scottish saints are known by nicknames, and familiar names, which express some quality about the which was much loved. St Kentigern, the missionary monk in Scotland, was also known as Mungo, which means “my dear one”.

It is also not impossible for an Egyptian to have found his way to Ireland in this period. We have already seen that there were well established trade routes, and there is a reference to other Egyptian monks, which we will consider shortly. In fact the Book of Leinster, a 12th century Irish manuscript, records St Eolang being commemorated at Aghabulloge, and this is clearly St Olan, and seems to be the same person as Corpmac. Other early records describe him as having been the tutor or instructor of St Finbarr, who died in 621 A.D., and he is indeed said to have had the alias name of MacCorbius. The Irish Life of St Finbarr corroborates this, and gives the name of his baptiser as MacCuirb.

One incident in the life of St Eolang/Olan/Corpmac is given in the Life of St Finbarr, where it is said…

Eolang placed Barra’s hand in the hand of the Lord himself on the site of Eolang’s tomb in the presence of angels and archangels, and said: ‘O Lord, receive this just man.’ Whereupon the Lord raised Barra’s hand to himself in heaven. However, Eolang then said: ‘O Lord do not take Barra away from me until it is time for his body to be released.’ The Lord then released Barra’s hand, and from that day on no one could look at the hand because of its brightness. That is why he always covered it with a glove.

We should not over-estimate the importance of this Egyptian monk in Cork. Locally he seems to have preserved a good memory, since his veneration remains to this day. But he did not have a wider influence beyond the instruction of St Finbarr, and by the early 7th century Ireland was already Christian.

It is not unreasonable that Olan the Egyptian should be found in Ireland, because there is another reference to Egyptians in the Felire of Aengus the Culdee, a long commemoration of the saints in poetic form which he composed in the early 9th century. It is interesting that this text notes various pilgrims who had come to Ireland from other countries, not so far distant as Egypt, such as the Saxons in Mayo, Cerrui from Armenia, those from Italy and Rome, and Gauls in various places. Among this list we find the verse…

Seven Egyptian monks in Desert Uilaigh, I invoke unto my aid through Jesus Christ.

This commemoration of the saints is very lengthy, and is refers to many who have come from other countries. These Egyptian monks are mentioned along with hundreds and thousands of others. They are not given any special importance or significance, beyond their origin, and the place where they were known. Some have suggested, entirely falsely and fancifully, that these seven monks brought Christianity to Ireland, but we would have to say that the mention of many more Saxons, and Romans, and even an Armenian, using the same logic, would apply to them as the founders of Christianity in Ireland. But in fact Ireland had already become Christian in the 5th century through the preaching of St Patrick and his companions. The text of Aengus is partly intended to show how others choose to come too Ireland, not that Ireland was in need of mission.

This commemoration of the saints is very lengthy, and is refers to many who have come from other countries. These Egyptian monks are mentioned along with hundreds and thousands of others. They are not given any special importance or significance, beyond their origin, and the place where they were known. Some have suggested, entirely falsely and fancifully, that these seven monks brought Christianity to Ireland, but we would have to say that the mention of many more Saxons, and Romans, and even an Armenian, using the same logic, would apply to them as the founders of Christianity in Ireland. But in fact Ireland had already become Christian in the 5th century through the preaching of St Patrick and his companions. The text of Aengus is partly intended to show how others choose to come too Ireland, not that Ireland was in need of mission.

Some have identified Desert Uilaigh with Dundesert, in Northern Ireland, where there are some remains of a Medieval Church and perhaps a monastery, but this is not conclusive by any means and archaeological excavation would be required.

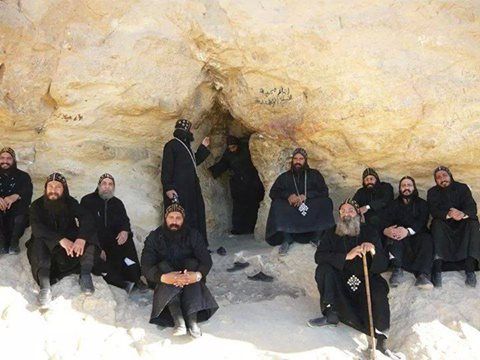

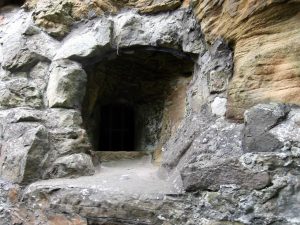

One final interesting reference to Egypt is found in the Life of St Serf, or Servanus. In the life written about him, many centuries after his death, he was said to have been born in the Eastern Mediterranean, and to have become a monk in Alexandria. The account of his life is embellished with rather impossible details, such as that he travelled to Rome and became the Pope there, before heading to Scotland. But it is not impossible that he had been born in the Middle East, and had been a monk, before making his way to the furthest extremities of the world. He established a monastic cell on St Serf’s Inch, or island, in Loch Leven, and is commemorated in St Serf’s Church, at Dupplin, and in other places in the area. Most importantly, on the coast near Kirkcaldy is the small settlement of Dysart, which has a cave, St Serf’s Cave, in which he is said to have prayed. It was still in use as a chapel until the Protestant period, and the name of the settlement has the meaning – a place of retreat, or a hermitage.

One final interesting reference to Egypt is found in the Life of St Serf, or Servanus. In the life written about him, many centuries after his death, he was said to have been born in the Eastern Mediterranean, and to have become a monk in Alexandria. The account of his life is embellished with rather impossible details, such as that he travelled to Rome and became the Pope there, before heading to Scotland. But it is not impossible that he had been born in the Middle East, and had been a monk, before making his way to the furthest extremities of the world. He established a monastic cell on St Serf’s Inch, or island, in Loch Leven, and is commemorated in St Serf’s Church, at Dupplin, and in other places in the area. Most importantly, on the coast near Kirkcaldy is the small settlement of Dysart, which has a cave, St Serf’s Cave, in which he is said to have prayed. It was still in use as a chapel until the Protestant period, and the name of the settlement has the meaning – a place of retreat, or a hermitage.

Certainly, by the time that the life of St Serf was written down, it still seemed possible that a monk could come to Scotland from Egypt, and perhaps he did.

We can see that there were few direct contacts between Egypt and the British Isles, and these were not significant. But the indirect influence of monastic spirituality was very important and did affect the development of Christianity in the British Isles, according to the local culture and to what seemed most useful. There were no Coptic missionaries in the British Isles, but there were a handful of monks, some known to us by name, and others unknown. And there were merchants and pilgrims passing back and forth over the centuries, reminding themselves and the British people, that there was a universal Church across the sea, of which it was a part.

7 Responses to "Coptic influence in the Early British Church"