St Thomas is referred to in each of the Gospels. In the Gospel of St Matthew 10:3 he appears in the list of the Twelve Apostles, where his name is given in the seventh place. His name in the Greek text is Θωμᾶς which is the transliteration of the Hebrew word meaning a twin. In the Gospel of St Mark 3:18 he is listed again as one of those whom the Lord ordained to be sent forth, which is the Greek verb ἀποστέλλω, or apostello. In the list of those disciples chosen to be apostles St Thomas is given as the eighth.

In the Gospel of St John we find that St Thomas features several times, and becomes more than a mere name. When our Lord was preparing to travel to Bethany to see the tomb of his friend Lazarus, even though it was clear that the Jewish authorities wished to apprehend him, it is written,

Thomas therefore, who is called Didymus, said to his fellow disciples: Let us also go, that we may die with him. John 11:16

St Cyril refers to this passage in his Commentary on the Gospel of St John. He says,

The language of Thomas has indeed zeal, but it also has timidity; it was the outcome of devout feeling, but it was mixed with littleness of faith.

St John Chrysostom is rather more frank, and while allowing that some have said that St Thomas was being brave when he spoke these words, nevertheless he considers them a manifestation of cowardice. He says,

Some say that Thomas himself wanted to die. But this is not the case. The expression is rather one of cowardice. And yet Christ does not rebuke him but instead supports his weakness. The result is that in the end he became stronger than them all – in fact, invincible.

St Thomas then appears in John 14:5, at the Last Supper, and he is forward enough to express his confusion at some of the things which Our Lord is teaching to the Apostles. Christ has said that he is going to prepare a place for his followers, and that they know the way he is taking. But St Thomas says,

“Lord, we don’t know where you are going, so how can we know the way?” John 14:5

St Cyril also comments on this passage and suggests that our Lord is almost forced into a situation where he must reveal what he does not yet wish to. But Christ ‘evades the excessive curiosity of his disciple’, and in his kindness gives an answer which provides them with a lesson they do need to learn at that time, saying, ‘I am the Way, the Truth and the Life’. Augustine also comments on this passage, and wishes us to consider that Thomas speaks falsely, yet without knowing that he does. He says ‘they knew, but they did not know that they knew’.

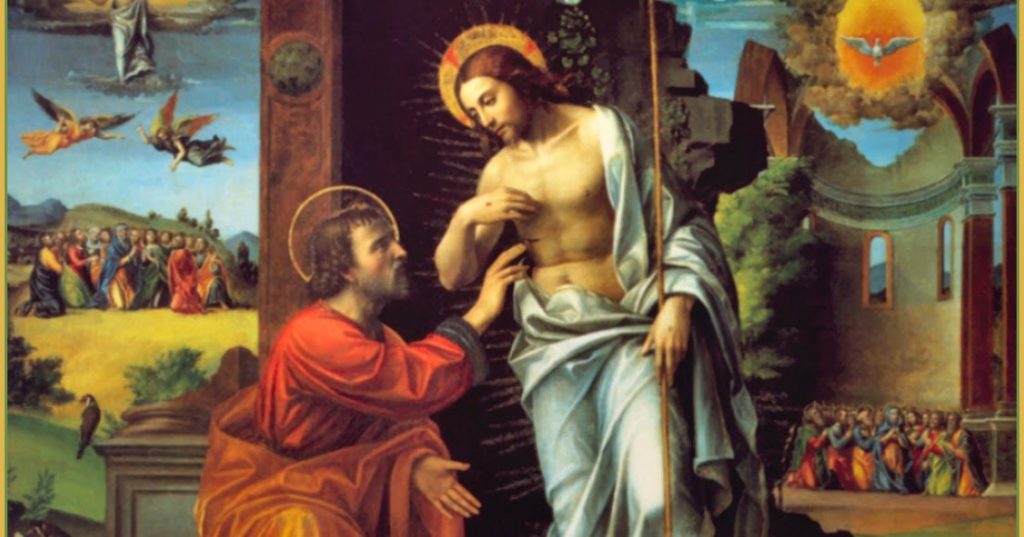

St Thomas finally appears in St John’s Gospel in the account of the appearance of our Lord to the disciples, in John 20. The doors of the place where they were gathered were shut, and then suddenly our Lord was among them, saying, ‘Peace be with you’. The Lord comforted them, and breathed upon them saying, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. Whose sins you remit they are remitted unto them, and whose sins you retain they are retained’. But Thomas was not with them.

This absence from such an important event has led some to suppose that St Thomas was deficient in some grace given by God, and go even so far as so suggest that he was not strictly an Apostle in the Church. Yet St Cyril is extremely clear, saying,

How then, someone may not unreasonably enquire, if Thomas was absent, was he in fact made partaker in the Holy Spirit when the Saviour appeared to the disciples and breathed on them, saying, “Receive the Holy Spirit”? We reply that the power of the Spirit pervaded every person who received grace and fulfilled the aim of the Lord who gave him to them. Therefore if any were absent, they also received him, the munificence of the giver not being confined only to those who were present, but extending to the entire company of the holy Apostles.

St Cyril also uses the example of Eldad and Medad, two of the seventy elders chosen by Moses. They were apart from the rest of the company when the Holy Spirit came upon the elders, but he came upon Eldad and Medad also, even though they were in the camp. Some of the examples of patristic references to St Thomas which follow will show that he was always and universally considered an Apostle, with the full authority and grace which all the other Apostolic community possessed.

St Thomas has been given the name of ‘Doubting Thomas’ because of his response to the report of Christ’s appearance to the others. He would not believe unless he saw the marks of the passion in the hands and feet and side of our Lord. Many of the Fathers refer to him having in some degree a lack of faith, though none seem willing to consider him faithless, but the same Fathers also show that God used his weakness to bring about a greater good. St Gregory the Great says that it was not an accident that he was not present, and that he should be given the opportunity of confirming our faith in the truth of the resurrection with his own. When our Lord appeared a second time, when Thomas was present, he gave him the opportunity of confirming his faith, as that of the other Apostles had been confirmed by his first appearance. We should remember that the disciples had already disbelieved the report of the women who came from the tomb, and it was only the presence of the Lord among them that convinced them. Origen points out that the other disciples had also been doubtful on occasion, and reminds us of the incident of Jesus walking on the water when they had all thought that it was a ghost or an apparition. Peter Chrysologus, bishop of Ravenna, gave a homily in which he wondered at the inquisitiveness of St Thomas, and how he dared to probe the wounds of our Lord. But he explains that not only was he curing his own uncertainty, but that of us all, and he was preparing a solid foundation in truth for his future service as a servant of the Gospel.

St John Chrysostom, in his homily on this passage, reflects that all through this period between the first and second appearances of our Lord, Thomas was being instructed by the reports of those who had been present, such that he longed to see the Lord, and desired greatly that what he was being told might be true. He describes how at his appearing to Thomas and the others, our Lord immediately addresses St Thomas’s doubts, showing that all through that period of waiting he had been divinely present, and knew already what Thomas desired. St Cyril links our reception of Christ in the Eucharist to this same narrative of St Thomas’ touching the wounds of our Lord, and calls us to avoid unbelief ourselves, and be rooted in faith.

There are a great many commentaries on this passage. It would seem that for many faithful Christians there is a sense of identity with St Thomas, who believes as best he can, and who is treated kindly and gently by our Lord, despite his doubts. He is rather impetuous and emotional, not entirely unlike St Peter. He is not afraid to ask the questions which the other disciples hide in their hearts. He receives grace to progress from saying, ‘I will not believe unless..’ to ‘My Lord and my God!’. He receives a full share in the Holy Spirit and in the Apostleship of the Church.

If we knew nothing more of this Apostle then we would already have many lessons to learn from those passages in which he appears in the Gospels. But in fact he does not disappear from the pages of history. The writings of the Fathers describe a consistent tradition, the basis of which need not be doubted as historical.

The earliest witness to a Christian tradition concerning St Thomas is found in the Acts of Thomas. This was a rather Gnostic document, though it was transmitted through a variety of Orthodox communities and in a variety of languages such as Syriac, Latin, Ethiopian and Greek. The most important aspects of the document for this brief study are the historical references which it makes. The Acts of St Thomas would appear to date from the end of the second century AD. They describe the Apostles gathering together and determining which area of the world each of them should take as the place of their missionary endeavours.

By lot, then, India fell to Judas Thomas, also called Didymus. And he did not wish to go, saying that he was not able on account of the weakness of his body, and said, “How can I, being a Hebrew, go among the Indians to proclaim the truth?” And while he was thus reasoning and speaking, the Saviour appeared to him during the night and said to him, “Fear not, Thomas, go away to India and preach the word there for my grace is with thee.” But he obeyed not, saying, “Wherever thou wishest to send me, send me, but elsewhere. For to India I am not going.”

Now it would seem that the author of this text has rather captured something of the psychology of St Thomas, and describes the sort of emotions which we might imagine him struggling with. Nor is he alone in such feelings of weakness. St Augustine of Canterbury shared exactly the same sense of fearfulness when he planned to abandon his mission to the English, and our Lord appeared to him in a similar way as is reported of St Thomas. Of course these Acts suggest to us that even an appearance of our Lord himself was not enough to persuade St Thomas.

We should also note from this passage in the Acts of St Thomas that he is referred to as Judas Thomas, and in the Syriac tradition from an early date it was considered that his name was Judas, since Thomas or Didymus simply means ‘the twin’.

In the Acts, St Thomas is sold as a slave by the Lord to a merchant from India, who had come from the King Gundafor, looking for a carpenter to work on his palace. Now this King Gundafor had been unknown to Western history, and as with many such references in ancient texts was assumed to be evidence that the Acts were not based on any historical facts. But in the 19th century examples of coins featuring this king were first discovered, and it became clear that he was the founder of a dynasty in North-West India, being succeeded by his brother, his nephew and then a more distant relation. The coins are dated to the first half of the first century. Gondophares, or Gundafor, describes himself as autokrator in Greek on his coins, and would appear to have been the ruler of an Indo-Parthian empire that stretched from modern Afghanistan into the Punjab. An inscription has also been discovered which refers to this king, and which appears to date his reign from 21 A.D. to perhaps 50 or 60 A.D. certainly within the lifetime of St Thomas.

Now this evidence does suggest strongly that the Acts of Thomas must have some basis in fact. There is no reference to this king in any later works in the West, and therefore no likelihood that a later writer should accidentally choose the same name as an unknown king and place St Thomas in connection with him. It seems entirely reasonable that this tradition must have originated very close in time and place to St Thomas and King Gondophares.

In the Acts we read that another king, Mazdei, sent messengers to St Thomas asking him to come and deliver his wife and daughter from demonic oppression. The narrative describes his journey and the incidents which take place in this other Indian kingdom, and then describe his martyrdom. This ancient text therefore allows us to conclude that at a very early date there was information which is at least accurate in regard to the name of an otherwise unknown king, which suggests that the St Thomas travelled to Parthia and North-West India where he was present in the court of King Gondophares, and that he then travelled to another Indian kingdom where he was martyred. The text describes St Thomas as an Apostle, and shows him establishing Christian communities in several locations and providing ministers in each place to serve the congregations of converts.

This would appear to agree with the information which Origen had several decades later. He writes saying, ‘When the holy apostles and disciples of our Saviour were scattered over the world, Thomas, so the tradition has it, obtained his portion in Parthia’. The Doctrine of the Apostles from the 3rd century also locates St Thomas’ mission in India. India and all its own countries, and those bordering on it, even to the farther sea, received the Apostle’s hand of Priesthood from Judas Thomas, who was Guide and Ruler in the Church which he built and ministered there”. In what follows “the whole Persia of the Assyrians and Medes, and of the countries round about Babylon…. even to the borders of the Indians and even to the country of Gog and Magog” are said to have received the Apostles’ Hand of Priesthood from Aggaeus the disciple of Addaeus.

Ephrem, composing hymns in the 4th century, writes about the relics of St Thomas being brought from India to Edessa, where they were enshrined. He says,

But harder still am I now stricken: the Apostle I slew in India has overtaken me in Edessa; here and there he is all himself. There went I, and there was he: here and there to my grief I find him. The merchant brought the bones: nay, rather! They brought him. Lo, the mutual gain! … But the casket of Thomas is slaying me, for a hidden power there residing, tortures me.

This hymn refers to the tradition, undoubtedly early, that the bones of the Apostle Thomas had been brought from India to Edessa. Indeed a feast is celebrated on July 3rd of ‘St Thomas who was pierced with a lance in India, and who body is at Edessa having been brought there by the merchant Khabin’. This form of martyrdom is consistent with that recorded in the Acts of Thomas. Another hymn of St Ephrem says,

A land of people dark fell to thy lot that these in white robes thou shouldest clothe and cleanse by baptism: a tainted land Thomas has purified. Blessed art thou, like unto the solar ray from the great orb; thy grateful dawn India’s painful darkness doth dispel. Thou the great lamp, one among the Twelve, with oil from the Cross replenished, India’s dark night floodest with light.

There are several other hymns by the same author about St Thomas. Together they show that in his time, the early 4th century, the relics of St Thomas were venerated in Edessa and were believed to have been brought from India by a merchant. It was understood that his mission had been in India, and that he had worked miracles there and established the Church, but that after his death, and the translation of his relics, such miracles continued to take place in India and now in Edessa.

Fathers from the 4th and 5th centuries continued to speak about St Thomas, and located his Apostolic ministry in India. Gregory Nazianzus says,

What? Were not the Apostles strangers amidst the many nations and countries over which they spread themselves?… Peter may indeed have belonged to Judea, but what had Paul in common with the gentiles, Luke with Achaia, Andrew with Epirus, John with Ephesus, Thomas with India, Mark with Italy?

Ambrose of Milan reports that Thomas has been sent to India, as does St Jerome, St Gaudentius, and St Paulinus of Nola. In the 6th century St Gregory of Tours describes St Thomas as having been martyred in India, and then his relics being removed to Edessa. Even the Venerable Bede, writing from the British Isles, records that India had been the scene of St Thomas’ labours.

These are not the local testimonies of the Indian Church, which it might be imagined were embellished over the centuries. But this is the constant witness of the Church. St Thomas was truly and entirely a member of the Apostolic band, and having been allocated the area of India as his mission he would appear to have hesitated and eventually found himself led there by the will of God rather than his own desire. He attended the court of King Gondaphares where he converted some of the residents, and then was called to another kingdom where he also won converts but was martyred by the thrust of a spear. In due course his relics were removed to Edessa, where they remained to be venerated by Ephrem of Syria, and to be known of by other Fathers of these early centuries. Since there is a mention of the relics of St Thomas being taken out of India, this would seem to suggest that the translation took place at an early date. Even if this is an interpolation rather than an original passage it would suggest that the translation was a known fact early in the transmission of the Acts of Thomas. Ephrem of Syria does not write of the translation as if it were a recent event and therefore it may be concluded that it took place before the early 4th century, and quite possibly early in the 3rd century.

This brief paper has only provided an overview of the scriptural and early patristic information about St Thomas. There is a great deal more which could be studied, especially from the Indian Orthodox traditions. But by referring only to the statements made by the Fathers it is possible to show that there is a universal Orthodox tradition that the Apostle Thomas established the Church in India, was martyred there, and that his relics were venerated from the earliest centuries in Edessa. Those who would doubt his Apostleship find themselves speaking against the weight of universal Church tradition and the explicit teaching of St Cyril.