Very often our adherence to particular phrases becomes no more than sloganeering and we lose any great interest in actually communicating what we believe or understanding what others might be saying. St Paul warns us against this in his first letter to St Timothy, when he writes, “Remind people of these things, solemnly urging them before the Lord not to dispute about words. This is in no way beneficial and leads to the ruin of the hearers.” We may easily become like the Pharisees when we think that insisting on particular words and terms is all that matters. This is a form of pseudo-Traditionalism which has the appearance of being rigorous and faithful to the Tradition, but in fact is an empty shell and a clanging cymbal with nothing fruitful within at all.

This is especially the case when we come to a Christological question such as do we confess one nature Incarnate or that Christ is in two natures. It would seem that a rigorous commitment to tradition requires us to insist on one or other of these phrases. but if we are not concerned with meaning both on our own part and on the part of those with whom we discussed these things then there is nothing traditional about us at all since the fathers of the church were concerned with what was meant and not only with what was said.

As soon as I say that I will write about the Christological faith of the Oriental and eastern Orthodox communions I will receive at least a few messages insisting that the Oriental Orthodox Church does not share the same faith as the Eastern Orthodox and is a completely different church, indeed no church at all. Most recently when I questioned someone who wrote in such a way and asked him to describe the substance of the differences between the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox faith, he stated that the Oriental Orthodox were unable to accept a Diophysite confession of Christ and were therefore not Orthodox at all.

I want to consider this accusation in this presentation, and I will suggest that in fact the Oriental Orthodox communion has a Diophysite understanding of Christology when we reflect on meanings and not simply hurl slogans at one another. This does not mean that the usual and traditional language of the Oriental Orthodox communion is not entirely valid within the context of its own lexicon. But it does mean that when we consider what the Eastern Orthodox communion mean in their Christology and what the Oriental Orthodox communion mean in their Christology we discover that we are saying essentially the same things though we are using different terms.

I have been an Orthodox Christian for 26 years, and have been a student of theology, and especially Christology, for 30 years. In respect of the Eastern Orthodox Christology I consider myself very well read, and with a good understanding. Certainly, good enough to compare and contrast the Oriental and Eastern Orthodox expressions. In respect of the Oriental Orthodox Christology, despite my many person faults and weaknesses, I consider myself an expert, and have written and taught about Christology extensively.

This presentation will not consider in great detail the history of the Christological controversy, but I will reflect on the basic and essential aspects of an Orthodox Christology and will use authoritative texts from the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox communion to consider whether the same ideas are being confessed. Since this particular presentation is concerned with an analysis from the perspective of the Eastern Orthodox and Diophysite position I will begin by asking what it is that the Eastern Orthodox wish to say about Christ.

A useful explanation is found in the Catechesis of Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, of the Moscow Patriarchate, published as The Mystery of Faith. He says about Christ…

The Fourth Ecumenical Council, convoked in 451 at Chalcedon, condemned Eutychian Monophysitism and proclaimed the dogma of ‘a single hypostasis of God the Word in two natures, divine and human’. According to the Council’s teaching, each nature of Christ preserves the fullness of its properties, yet Christ is not divided into two persons; He remains the single hypostasis of God the Word.

This belief was expressed in the Council’s dogmatic definition: ‘…We confess one and the same Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, perfect in Divinity, perfect in humanity, truly God, truly human being, with a rational soul and body, consubstantial with the Father in His Divinity and consubstantial with us in His humanity.., one and the same Christ, the Son, the Only-begotten Lord, discerned in two natures without confusion, without change, without division, without separation’.

Four terms were used to convey the union of the two natures, ‘without confusion, without change, without division, without separation’, and each was strictly apophatic.

It is important that we start here, because this represents the measured views of a contemporary senior bishop of the Eastern Orthodox Communion. When we are engaged in discussion it must begin with those who are present with us and to us. This explanation of Metropolitan Hilarion is authentically Orthodox according to the Eastern Orthodox and represents the essential aspects of an Eastern Orthodox Christology. Of course, it is not a statement made in isolation, and quite naturally, Metropolitan Hilarion references the statement of the Council of Chalcedon. This is not a problem when the goal is mutual understanding rather than mutual denunciation.

What does Metropolitan Hilarion say? How can we break down his statements to get the essential aspects of the Eastern Orthodox Christology without resorting to simplistic slogans? I think that the bullet points he presents are these:

- There is a single hypostasis of God the Word

- This single hypostasis is both divine and human

- The divinity and humanity preserve their properties

- Christ is not two persons

- Christ is the single hypostasis of God the Word

- The divinity of Christ is perfect

- The humanity of Christ is perfect

- Christ is consubstantial with the Father in his divinity

- Christ is consubstantial with us in his humanity

- The humanity and divinity are united

- The union is without confusion, without change, without division, without separation

I think this is a reasonable list of essential characteristics based on the statement of Metropolitan Hilarion, and his use of the definition of Chalcedon. The issue here is not whether or not Chalcedon is an authority for Oriental Orthodox, nor it is the issue of whether or not some of those at Chalcedon held heterodox positions. The issue is, and must be to begin with, how does the contemporary Eastern Orthodox communion express their Christology in the light of Chalcedon and the later councils which they organised.

Indeed, the Eastern Orthodox Christological position can surely be reduced, to make the necessary argument clear, to the statement that Jesus Christ is the one hypostasis of God the Word, who has become perfect man while remaining God, without change or division, so that he is consubstantial with the Father in his divinity and consubstantial with us in his humanity.

This is essentially the Diophysite Christology. It wishes to emphasise that Jesus Christ, who is God the Word, is truly and perfectly human, while remaining truly and perfectly divine. It describes a unity in Christ who is the one hypostasis or identity or subject of God the Word, while also expressing a duality, without separation and division, of humanity and divinity. When the Eastern Orthodox communion speaks of Christ being in two natures, whatever others might have meant in the past, they mean to refer to the reality of the humanity and divinity in Christ.

The issue here is not about what might be the best way of describing Christ but what is actually believed by the Eastern Orthodox communion in their Christology. In the same way, as I now begin to compare authoritative statements by Oriental Orthodox fathers with these different points, is not whether the same terminology is exactly used but if the same meaning is expressed. Therefore, I will especially be using passages where the fathers of the Oriental Orthodox communion are seeking to go beyond phrases and technical terminology and actually describe what they mean.

I want to begin by looking at some passages from the Henotikon of the Emperor Zeno, published by him in 482 A.D. in an attempt to bring about unity in the church between those who accepted the council of Chalcedon and those who rejected it. I am referring to it here because on the side of the Oriental Orthodox, which is a shorthand way of referring to those who rejected the council of Chalcedon, it was accepted as a statement of Christology but those who did reject it did so on the basis of it failing to condemn Chalcedon and not because they disagreed with the Christology presented in it.

It says…

We moreover confess, that the only begotten Son of God, himself God, who truly assumed manhood, namely, our Lord Jesus Christ, who is consubstantial with the Father in respect of the Godhead, and consubstantial with ourselves as respects the manhood; that He, having descended, and become incarnate of the Holy Spirit and Mary, the Virgin and Mother of God, is one and not two; for we affirm that both his miracles, and the sufferings which he voluntarily endured in the flesh, are those of a single person: for we do in no degree admit those who either make a division or a confusion, or introduce a phantom; inasmuch as his truly sinless incarnation from the Mother of God did not produce an addition of a son, because the Trinity continued a Trinity even when one member of the Trinity, the God Word, became incarnate.

It is interesting that this document which was accepted by those on both sides as representing an Orthodox Christology anathematised both Nestorius and Eutyches and this was without any difficulty on the part of the Oriental Orthodox who had never followed Eutyches nor had we considered him a father in our communion at all. The history of this text deserves a different presentation, and it is referred to here because it represents the Christology of the Oriental Orthodox at this period, just a few decades after the council of Chalcedon. It was written by Acacius, the Chalcedonian Patriarch of Constantinople, and it was approved by those who rejected Chalcedon, as far as it went. Even Severus of Antioch accepted it as far as a statement of Christology, though he criticised it for failing to deal with Chalcedon.

What do we find?

The only-Begotten Son, truly God, became man, Jesus Christ, and is consubstantial with is us in his humanity and consubstantial with the Father in his divinity. He is one and not two, and all of his human experience belongs to one person. Both a division between the humanity and divinity, and a confusion of the divinity and humanity, are rejected. It was God the Word himself who was made man, and so there is no other person, no man named Jesus, who has become part of the Holy Trinity.

There is no reference in the Henotikon to either one nature incarnate, or that Christ is in two natures. But the key elements are certainly and clearly present. There is only one person, God the Word, who has become incarnate, and is the Lord Jesus Christ, and this one person is consubstantial with the Father in his divinity, and consubstantial with us in his humanity, without separation or confusion.

To a great extent this seems to cover all of the 11 points which I began with gathering from the passage of the book by Metropolitan Hilarion. This is a Diophysite Christology which is being expressed, we can certainly say. By that I mean, as I have said, that it is consistent with the understanding and expression of the Christology of the Eastern Orthodox communion.

What about some of the actual writings of the Fathers of the Oriental Orthodox communion, rather than a text to which many of them subscribed. Philoxenos was an important bishop in the period between Chalcedon and the Emperor Justinian. In his Letter to the Emperor Zeno, written at about the same time, we find these sentiments…

God the Word emptied Himself and came into the womb of the Virgin, without leaving the Father, without separating Himself from Him with Whom, near Whom, and like unto Whom He always is. For we believe that, in so far as He is God, He is everywhere, that is, like the Father and like the Holy Ghost.

This first passage shows us that Philoxenos considers Christ to be God the Word who remains God, even in the incarnation.

He continues…

He wished to give life to men by His abasement, His embodiment, His passion, His death, and His resurrection. And He came to the Virgin without ceasing to be everywhere, and He was embodied in her and of her, and became man without change. For He did not bring to Himself a body from heaven as the foolish Valentinus and Bardesanes assert; nor was His embodiment from nothing, because He did not wish to redeem a creature that did not exist, but He wished to renew that which, created by Him, had become old.

In this passage we see that Philoxenos wishes to insist that the Word was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and in her, and he indeed became man, without any change at all, and without ceasing to be God. Nor was this humanity from heaven, or created from nothing, but it was of our own humanity, from the Virgin Mary, so that our own humanity might be redeemed.

Then he says…

We do not hold that the Word became man with a change in His nature, because God is not capable of change, change being a modification of things created; but, as He exists without having begun, so also He was not changed by becoming man. For He became man by taking a body, and not by assuming a man whom He caused to adhere to His person; otherwise, we would be introducing an addition into the Trinity, and would be found to admit a son of grace, outside the Son of nature.

The Word could not change when he became man, because God is not capable of change. Change only belongs to created things. He became man, truly, by taking a body for himself, and not by joining himself to a man, because this would certainly introduce another person into the Trinity.

All of this consistent with some of those points produced earlier. It is the Word of God himself who has become truly man of the Virgin Mary, to be consubstantial with us, as he is consubstantial with the Father, and he has not changed in becoming man.

He repeats this idea saying…

The Word, therefore, became something that He was not and remained something that we were not… For we became sons of God. although our nature was not changed, and He became man by His mercy, although His essence was not changed.

He became something he was not, that is man, while remaining what he was, that is divine, and his essence was not changed. This is consistent with what we have said of the definition of Diophysite Christology.

Then he says…

I confess, therefore, one only person of the Word, and I believe that this same person is also man, that is, God Who became man; not that He dwelt in a man, not that He built to Himself a temple in which He dwelt. … I see, with the eye of faith, a Spiritual Being, Who, without change, became corporal, and Mary brought forth, not a double Son, as Nestorius said, but the Only-Begotten embodied, Who is not indeed half God and half man, but wholly God because He is from the Father, and wholly man because He became man of the Virgin.

There is a lot of substance in this passage. We can see that Philoxenos confesses one person of the Word, which is one of the necessary requirements for a Diophysite Christology. He confesses that the one person of the Word is also man. Not God dwelling in a man, but truly God made man. This is another necessary requirement. And this one person, God the Word became man without change. This is another requirement. And God the Word made man is not half God and half man, but perfect God and perfect man. This is a central aspect of Diophysite Christology. And this man that he became is man like us because he became man of the Virgin Mary.

He continues…

I confess that there was a union of the natures, that is, a union of the divinity and the humanity, and I divide neither the natures nor the persons, nor the parts of this and that, which have been united in an ineffable manner. I do not see two things where they became one, nor do I admit one where two are known to be. … we believe that the body belongs to Him, because He was made man, then corporeity is the property of the person of God, and not of another human person.

This is where he speaks about the unity of the humanity and divinity. Firstly, in accordance with Diophysite Christology, it is necessary for him to say that a unity has taken place. He does not want to divide, and the Diophysite expression of Christology also insists that there is no division. But equally he will not allow any confusion... I do not see two things where they became one, nor do I admit one where two are known to be. What is the one that he sees? It is that the divinity and the humanity both belong to one person, to God the Word who is incarnate without change. There is a unity here. The humanity is the humanity of God the Word and not some other person. But he insists that there are two which are known to be. What is the duality? It is in the humanity and divinity, which are not the same thing at all, but which are brought to unity by belonging to the one person.

Then he says…

The person of the Son, therefore, became embodied by the will of the Father and of the Holy Spirit, and His embodiment does not exclude that He may be believed consubstantial with them, for He was begotten Son by the Father and He was born Son of the Virgin. … And we believe that the Same is Son by two generations, and that He, to Whom belong the name and fact of Son from the Father, became truly the Son of the Virgin; for to Him indeed belong these two things «to become and to be born», and because He was Son, He was born Son, that is, in becoming man without changing.

The Son has two generations, or beginnings, and this is also necessary to the Diophysite Christology. He was begotten of the Father, and he was born of the Virgin. It is the same Word of God, the Son of the Father, who was truly born of the Virgin Mary and became man without change.

This humanity and divinity without change is described when Philoxenos says…

We confess, therefore, that the Virgin is Theotokos, and we believe that the embodied Word, after being born of her corporally, was wrapped in swaddling clothes, sucked milk, received circumcision, was held on His Mother’s knees, grew in stature and was subject to His parents, all this just as He was born. He did not need to be fed Who feeds others, since He is known to be God, but He became subject to all this because He was made man, although perfect and complete in His nature and in His person.

The Virgin Mary is Theotokos because the one whom she bore is truly God the Word, but he became truly man and as he was truly born in a human way, he was clothed in a human way, and sucked milk and was circumcised in a human way, and he grew as a child in a human way. This was not of necessity but because being God he chose to become man and was perfect and complete in his own divine nature.

Both the glory and the suffering belong to the one Word of God who is incarnate, another of the necessary principles of the Diophysite Christology. This same duality in union is described when Philoxenos says…

To Him belongs greatness by His nature; and humiliation, because He emptied Himself. The things of the Father are His, because He has the same essence; and ours are His, because He became like unto us. To Him honour, because He is the Lord of glory; to Him humiliation, because He revealed Himself in the flesh. His the fact that He was hungry, and His the fact that He multiplied bread. He was hungry, and thereby showed that He became like unto us; He fed the hungry, and thereby showed that the power remains to Him. For His nature was not changed when He became man, nor was the strength of His power diminished.

In this passage we see the continuing reality of the humanity and divinity is essential to Philoxenos, but it is a reality that belongs to the one Word of God, who acts with both humility and power in and through his own humanity. He has the same essence as the Father, and this suffers no change in the incarnation, but he also properly experiences his own humanity in hunger and exercises his own power in multiplying bread. He is himself both God and man, the things of the Father and the things that our ours both belong to him, as the Diophysite Christology describes.

Coming to his conclusion Philoxenos says…

We do not therefore subject the nature of the Word to passion; nor do we believe that a man distinct from Him died. But we believe that He Who, as God, is above death, experienced it as man. We believe that He is the Only Begotten Son, one of the Trinity, as is clear from His own words to His disciples: “Go forth, teach all nations, and baptize them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.”

What do we find here? It is that the divinity of the Word of God does not suffer. This is what the Diophysite Christology insists upon. But we also see that it was not a man distinct from God the Word who died. This is also consistent with the Diophysite Christology. God the Word nevertheless experienced death in his own humanity, while being above death in his divinity. This also seems to be exactly what Diophysite Christology wants to say about Christ.

The final statement in this expression of his Oriental Orthodox faith, is provided in the condemnation of various heresies in which Philoxenos says…

…Not taking anything from the Trinity, as the foolish Sabellius and Photinus have thought to do, nor dividing its persons, like Arius and Macedonius, nor adding another person to the Trinity, as Theodore and Nestorius have imagined, nor saying that one of its persons suffered a change, like Apollinaris and Eutyches… I also say anathema to Eutyches the heretic, and to his followers, because he denies that there was a real embodiment of God from the Virgin and regards as hallucinations the mysteries of His corporeity.

Philoxenos not only rejects the Trinitarian errors which diminish the Son and the Holy Spirit or deny the Holy Trinity altogether. But he also rejects the Christology of Nestorius and Theodore, which he understood to divide Christ, and make him dwell in a man, as well as any idea that there was a change in the incarnation of the sort that Apollinarius and Eutyches taught. Indeed, he condemns Eutyches, and his denial that Christ, the Word of God, had become truly human. This is all necessary to the Diophysite Christology, and it is all expressed here in the writing of Philoxenos just 30 years after Chalcedon.

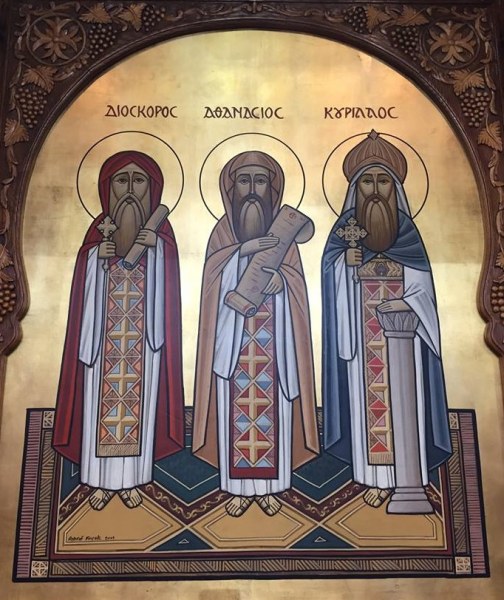

Even at the time of Chalcedon, in the writings of Dioscorus from his exile in Gangra, where he died. We find him saying…

I am fully aware, having been educated in the Faith, respecting Him, Christ, that He was born of the Father, as God, and that the Same was born of Mary, as Man. Men saw Him as Man walking on the Earth and they saw Him, the Creator of the Heavenly Hosts, as God. They saw Him sleeping in the ship, as Man, and they saw Him walking upon the waters, as God. They saw Him hungry, as Man, and they saw Him feeding (others), as God. They saw Him thirsty, as Man, and they saw Him giving drink, as God. They saw Him stoned by the Jews, as Man, and they saw Him worshipped by the Angels, as God. They saw Him tempted, as Man, and they saw Him drive away the Devils, as God. And similarly of many (other) things.

In this passage from one of his letters we see clearly that he taught that Christ was Begotten of the Father as God and born of the Virgin Mary as man. This is a Diophysite Christology. After the incarnation he remained both God and man. He was both hungry as man and he fed the crowd as God. More than that, he also adds…

He became Consubstantial with Man, taking Flesh, although He remained unchangeably what He was before.

Clearly Dioscorus insists that Christ, God the Word, was consubstantial with us in his humanity. But he also remained without change, God the Word. And in another letter, so that we can be sure what he taught and believed himself, we find…

This I declare, that no man shall say that the holy flesh, which our Lord took from the Virgin Mary, by the operation of the Holy Spirit, in a manner which He Himself knows, was different to and foreign from our body…

I will break up this passage into short sections to be clear what he is saying. The humanity of the Lord Jesus was from the Virgin Mary and by the Holy Spirit, and it was not at all different to our own humanity. This is essential to the Diophysite Christology, and it is what Dioscorus is teaching.

And again,’ It was right that in everything He should be made like unto His brethren,’ and that word ‘in everything’ does not suffer the subtraction of any part of our nature : since in nerves, and hair, and bones, and veins, and belly, and heart, and kidneys, and liver, and lungs, and, in short, in all those things that belong to our nature, the flesh which was born from Mary was compacted with the soul of our Redeemer, that reasonable and intelligent soul, without the seed of man, and the gratification and cohabitation of sleep.

This humanity, Dioscorus insists, was lacking nothing at all which belongs to our human nature. Nothing at all. Whatever it means to be human, that is what God the Word assumed in becoming human. Nor did he lack will, which is expressed at this time in the idea of a reasonable and intelligent soul. He lacked nothing. He became entirely human as we are human. This is what the Diophysite Christology insists, and it is what Dioscorus insists. God the Word has become a man, just like us in every way, while remaining God. Then he says…

For He was like us, for us, and with us, not in phantasy, nor in mere semblance, according to the heresy of the Manichaeans, but rather in actual reality from Mary, the Theotokos… He became man, and yet He did not destroy that which is His nature, that He is Son of God; that we, by grace, might become the sons of God. This I think and believe; and, if any man does not think thus, he is a stranger to the faith of the apostles.

It was not a mere appearance. It was not a ghostly form which he used. But God the Word became in actual reality, like us, from the Virgin Mary who is Theotokos, and he became man without change.

Elsewhere Dioscorus has insisted…

We speak of neither confusion nor division nor change. Anathema to whoever speaks of confusion or change or mixture.

This is what the Diophysite Christology also insists. Neither confusion, division nor change. Perfect in divinity and perfect in humanity, our own humanity, lacking nothing which is according to the human nature.

Abba Paphnutius visited Dioscorus in his exile. We can note how the monk speaks to him and refers to the humanity and divinity of Christ.…

I have seen the bush in which is the Messiah, that is to say his flesh, the divinity was united to it without change and without confusion, as the bush which burned without being consumed, in the same way the divinity and the humanity were not separated the one from the other from the moment when He entered into the womb of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God. Glory to Him, whose name is worshipped unto ages of ages, Amen.

He uses the image of the Burning Bush as an analogy for the incarnation. The humanity and divinity were united just as the bush was burned without being consumed. In the same way, the humanity and divinity in Christ were neither divided, but neither was there any change or confusion. This is the Diophysite Christology, that there is one God the Word who is incarnate, and his perfect humanity and perfect divinity are neither divided, nor confused or mixed.

In the fifth and sixth centuries we can turn to the confessions of some of the great Fathers of the later period. At a council held in Ephesus in the years after Chalcedon, 700 bishops, under the leadership of the non-Chalcedonian Timothy of Alexandria, signed a statement which said…

We join with them in anathematising Nestorius, and everyone who does not confess that the only-begotten Son of God was incarnate by the Holy Ghost, of the Virgin Mary; He becoming perfect man, while yet He remained, without change and the same, perfect God; and that He was not incarnate from Heaven in semblance or phantasy.

These are all statements which express the key aspects of the Diophysite Christology. God the Word was incarnate, and he became perfect man, while remaining perfect God. His humanity was of the Virgin Mary and he did not have a ghostly body, but one just like us, complete and perfect in every way.

Later still, Severus of Antioch, after his exile under Justinian, wrote to Anthimus, Patriarch of Constantinople, describing his faith. He says…

The Lord, the everlasting God, whose merciful Word became incarnate and became man, that is, in order that the second Adam might in truth die the death that had prevailed over us and overthrow its eternal dominion, a death which it was not possible for impassible and immortal flesh to endure, because that which is impassible and immortal is not capable of suffering and dying. For, if He did not die our death for our sins and destroy this death in flesh resembling our passions when He rose from the dead, we are strangers and alien to the benefit of the Resurrection.

There are some important ideas here. I will try to pick out those which represent the Diophysite Christology. It is God the Word himself who has become incarnate and become a man, and he needed to become truly human as we are since he intended to become a Second Adam, and die our own death to save us from its power. If he did not become human as we are then his suffering and death were not for our salvation. Therefore, it was necessary, as the Diophysite Christology describes, that God the Word become truly human, just like us, or we are not saved.

This is really the substance of the Oriental Orthodox Christology. If God the Word had not become a man like us, complete in every way, then we are not saved. Severus adds…

The incarnate Word of God of His own will endured the assay and assault of human and natural and innocent passions. And the signs, even the human ones, He utters in a divine fashion, and performs some of them in a manner befitting God and some in human fashion.

What does he mean here? It is that God the Word experienced our human life, he was really human, but he was not only human, because he was God and man, without confusion, but also without division. So, we see that he experiences some things as a man, his hunger and tiredness, but we also see that his divine power is also expressed, such as the multiplication of bread.

Theodosius, Patriarch of Alexandria at the same time, writes in a letter describing his own faith, and says…

I confess that God the Word, of the nature of the eternal Father, Light of Light, Very God of Very God, became incarnate and also became man by the Holy Spirit and of Mary the ever-virgin, in flesh endowed with a soul and an intellect after our nature, and was made like unto us in everything except sin.

God the Word is truly God according to his divine nature and is consubstantial with the Father. He is true God of true God. But he has also become man, in the humanity which he received from the Virgin Mary, and this humanity is lacking nothing at all of our humanity, including soul and intellect, which represents the human faculty of will, before that idea had become controversial. The humanity of Christ is just like ours, thinking, reflecting, willing. He has become entirely human in everything, except sin. This is what the Diophysite Christology requires. Then he continues…

For it was right and just that the nature which was vanquished in Adam should in Christ put on a crown of triumph over death. … But, if we were vanquished in another nature, and the Word of God did not partake of it or make the same flesh which was assumed from us and personally united to Him impassible and immortal through the union with Him, as some foolishly say, our faith is vain, … but in a body which was passible and of our nature He suffered innocent passions, and underwent death, and trampled on the sting of sin, and dissolved the power of death.

There can be no doubt, Theodosius is insisting as a matter of dogma and salvation, that God the Word became a man in our own humanity. If it is a different sort of humanity, then our faith is useless. But he and we insist, God the Word became man, in our own humanity, and in our own humanity, which he made perfectly and completely his own, he suffered and died and destroyed the power of death.

And he concludes saying…

Christ, who consists of the two elements, the Godhead and also the manhood, which have a perfect existence, each in its proper sphere, is one and is not divided; and the union is not confused in Him in that He united to Himself personally flesh of our nature and allowed it in all the dispensation to be passible and mortal but the same was holy without sin, and by the Resurrection made and rendered it impassible and immortal and in every way incorruptible.

Here again we see that there is no problem in recognising the duality of Christ at the proper level. There are these two elements of which Christ consists. There is the divinity and the humanity. These have a perfect existence in their own natural expression. But even though these are different we do not divide Christ, for he is one, in his humanity and his divinity. They are not confused, the humanity and divinity, even though the one Christ, God the Word, united humanity to himself. But each has a perfect existence in a union without confusion or division.

This is what the Diophysite Christology wants to insist on, whatever terminology is used. And this is what the Oriental Orthodox Christology expresses, whatever terminology is used.

What else does Severus say…

Emmanuel is one, consisting of Godhead and manhood which have a perfect existence according to their own principle, and the hypostatic union without confusion shows the difference of those which have been joined in one in dispensatory union, but rejects division.

This is a clear statement of the teaching of Severus. There is a clear duality of divinity and humanity in Christ, nor is this problematic. Indeed, the union of humanity and divinity must take place without confusion. But this union does not hide the difference of the humanity and divinity, which is preserved. Rather it is concerned only to prevent division. It is necessary to find a unity in the divine person of the Word of God who has become incarnate without change, while also preserving the integrity of the humanity and divinity which continue to have a perfect existence after the incarnation.

This is again entirely what the Diophysite Christology insists upon, whatever terminology is used. I will add just a few more references from Severus to show that he, and the Oriental Orthodox following him to the present day, insist on the humanity and divinity of Christ being present and retaining their integrity in the incarnation. He says here…

Cyril of Alexandria says, “For between Godhead and manhood I also allow that there is great distinction and distance: for the things which have been named are clearly different, and in no point like one another”. This then is the difference that appears in natural characteristics, the different principle underlying the existence of Godhead and manhood: for the one is without beginning and uncreated, and bodiless, and intangible, while the other is created, and subject to beginning, and temporary and tangible, as being flesh and solid. This difference we in no wise assert to have been removed by the union.

Severus is agreeing with the words of Cyril of Alexandria, who insists that the divinity and humanity are entirely different from each other. We can see that one is uncreated and the other is created, for instance. The important point, in relation to a Diophysite Christology, is that Severus insists himself that this difference is not removed in the incarnation. It is not removed, so that the divinity remains the divinity and the humanity remain the humanity. This is entirely what the Diophysite Christology, outlined at the beginning of this presentation, requires. The particular terminology is not so important. What matters is what is meant and what is meant is clearly the same.

I will add a few additional references from Severus, since some will wish to say that the Oriental Orthodox accept all these aspects of the Diophysite Christology but insist on a Christ with no human will, and therefore not like us at all. But Severus says…

He is indeed one from two, from divinity and humanity, one person and hypostasis, … become flesh and perfect human being. For this reason, he also displays two wills in salvific suffering, the one which requests, the other which is prepared, the one human and the other divine.

This seems very clear. He is divine and human, while being one person. He has become a perfect human, lacking nothing, and this includes the human faculty of will. He has two wills, in this important sense, one human and one divine.

Elsewhere he says…

From the time of swaddling clothes, before he came to an age of distinguishing between good and evil, on the one side he spurned evil and did not listen to it, and on the other he chose good. These words ‘he spurned’ and ‘he did not listen’, and on the other ‘he chose’ show us the Logos of God has united to himself not only to the flesh but also to the soul, which is endowed with will and understanding, in order to allow our souls, which are inclined towards evil, to lean towards choosing good and turning away from evil.

What does he say here? It is that this perfect humanity which he united to himself, he chose the good in it. He chose the good because he had the human faculty of will as Severus states. He had a human soul endowed with will and understanding so that our own human soul with a corrupt and confused will might be redeemed.

What were those points I described at the beginning as being the essential aspects of the Diophysite Christology?

- There is a single hypostasis of God the Word

This is certainly the case in the teachings of the Oriental Orthodox communion. Jesus Christ is God the Word and there is no other person or hypostasis in Christ.

- This single hypostasis is both divine and human

We have certainly seen throughout this presentation that this one person or hypostasis of God the Word has become man while remaining God, and that this belief that the Word has become man and remains God and man is found throughout the materials presented from the Oriental Orthodox.

- The divinity and humanity preserve their properties

This has also been explicitly stated in the various texts I have used, nor are these unusual. It would be possible to produce hundreds of such references insisting that the divinity and humanity are not changed, or mixed.

- Christ is not two persons

This has also been stated clearly. Indeed, one of the main aspects of the Christological controversy from the Oriental Orthodox perspective has been a rejection of any idea that Christ is two persons, God the Word, and a man called Jesus.

- Christ is the single hypostasis of God the Word

This has also been expressed throughout these references. Jesus Christ is the one hypostasis of God the Word.

- The divinity of Christ is perfect

In almost every reference it is clear that the divinity of Christ is considered to be perfect, unchanged, not half God, as Philoxenos puts it, but perfectly God.

- The humanity of Christ is perfect

And in the same way, the humanity of Christ is perfect. It must be perfect. It must be the same as our own, apart from sin, otherwise we are not saved, and it does not lose its integrity in the incarnation. The human soul of Christ has will, just as we have. Nothing is lacking. Nothing is missing.

- Christ is consubstantial with the Father in his divinity

The divinity of Christ is the same divinity as belongs to the Father. It has not changed. It has not diminished. It has not become something other than it was.

- Christ is consubstantial with us in his humanity

And in the same way the humanity of Christ is of the same humanity as us. It is not lacking anything. It has not been diminished either, or changed, or mixed, or become something else. In everything it is the same as our humanity and it remains the same as our humanity.

- The humanity and divinity are united

But the humanity and divinity are united. Christ is not only a man. But he is truly man. He becomes hungry, but he remains God, and with his own human mouth he speaks divine words, and with his human hands he breaks bread and multiplies it for a crowd. He is, and remains, God who has become man while remaining God.

- The union is without confusion, without change, without division, without separation

And this unity of humanity and divinity does not change either. Does not allow a separation into God and a man, nor does it permit a confusion or mixture so that Christ is neither one thing nor another. This is what has been insisted upon throughout these passages from Oriental Orthodox Fathers.

Certainly, a different terminology is preferred on both sides. I have not investigated the different language used by each community. Rather I have considered what is actually meant. And in considering what is meant, it seems very clear, that the same things are meant. The last 25 years of detailed study which I have invested in the Christological controversy bear this out. If all of these things I have described are what define Diophysite Christology, and I have no doubt they are, then the Oriental Orthodox have a Diophysite Christology. And if we have a Diophysite Christology in this sense, a real sense, the only meaningful sense, then progress towards reconciliation becomes a divine imperative, and not a niche interest.

As St Paul teaches us…

Do not dispute about words. This is in no way beneficial and leads to the ruin of the hearers.

One Response to "The Diophysite Christology of the Oriental Orthodox"