Summary

This translation into English is of the introductory article and the text of the Presanctified Anaphora of St Severus of Antioch. It was publsihed in French in 1919, and I have translated it here into English. A Presanctified Liturgy is one in which a chalice of wine is consecrated by a portion of the holy Body of the Lord which has been preserved from a Liturgy taking place on another and earlier date. In the Syrian tradition this form of service did not become established, as it had among the Greeks. In later times the idea of a presanctified communion, as the introductory article describes, became restricted in the Syrian tradition to a priest on his own, and he was permitted to use whatever prayers he found appropriate. But the liturgical text here was for a public service of communion, with priest, deacon and faithful. It was much shorter than a normal Liturgy, as can be seen from the text and was usually intended for use during Lent, when weekday Liturgies were forbidden.

Text

Introductory Article

The liturgists do not yet know a Syriac Anaphora for the Mass of the Presanctified. Renaudot complained in these terms: “Quamvis in Oriente Proesanctificatorum Missa celebretur graeco more, singulare tamen illus officium a nobis hucusque nec in Syrorum, nec in Coptitarum codicibus repertum est … Apud Syros, in tanto liturgiarum number, nulla similis (Liturgiai Praesanctificatorum Divi Marci). So it is a gap that the absence of this office in his Collection of Oriental Liturgies. This gap, the Western authors who followed them, failed to fill. If, indeed, they offer a word concerning the Mass of the Presanctified in the various other churches, they report with difficulty on the Syriac-speaking churches.

Their silence is, however, more understandable than that of the Syrian liturgists. While they treat ex-professo of the Mass, the latter omit to speak of the Presanctified. The holy and learned Maronite Ad-Douaihi (died in 1704), is equal in this to the Jacobite Bar-Salibi (died in 1171).

In the liturgical books, too, one would search in vain for the Anaphora of the Presanctified. The missal of the Syrian Catholics, published in Rome in 1843, does not contain it. The same must be said of the Maronite missal, in spite of appearances: The Anaphora which it assigns to the Mass of the Presanctified is, in fact, an adaptation, in this mass, of the Anaphora called “Charrar”….

We have had the good fortune to find, in a Syriac manuscript of the National Library, a single Anaphora composed for the Mass of the Presanctified; we present it to the public.

The Mass of the Presanctified, as we know, is only the communion, apart from the divine sacrifice, from a host a consecrated one or more days before. The ceremony is the same as that of communion in the ordinary Mass; it begins at the Sunday prayer; all that precedes, preface, consecration, epiclesis, anamnesis, in a word, all that pertains to the Sacrifice is replaced by the rite of the consignation of the chalice with the pre-consecrated, and pre-sanctified host.

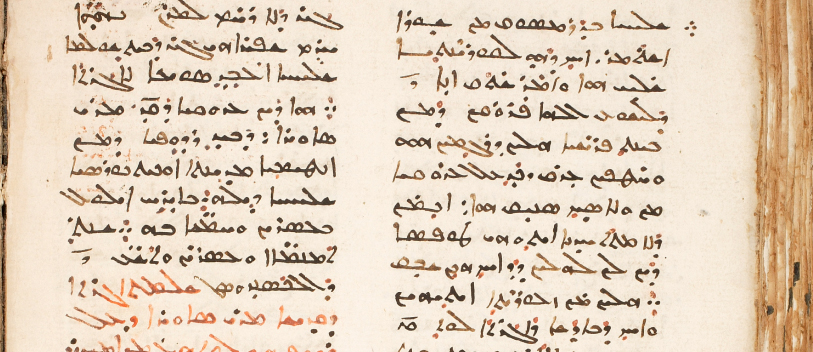

This rite, which characterizes the Mass of the Presanctified, is given, among the Syrians, this name. In the Maronite missal it is titled “Consignment of the Chalice.” Our manuscript does not title it otherwise. This manuscript is No. 70 of the Syriac Collection of the National Library (Catalog Zotenberg, 1874) and is written on small vellum paper, in Estranghelo script, and the scribes who produced it have made it with all the more care, since they intended it, they tell us, “for their personal use during their life, and after their death to their good memory.” It was “Jacques, priest, his brother David and their father Michel, of the village of Abraham, dependent on the city of Melitene.” They finished it in the year 1370 (1059 AD) of the Greeks. The title it bears is – a book or a manual of the priest.

The Syriac Collection of the British Museum contains a large number of manuscripts that have the same title. They are fifteen. In taking them together, they contain, like ours, a choice of Anaphora, prayers for the divine service and finally extracts from the ritual – notably the Ordo Baptismi, which the manuscript of the National Library does not contain. So there is a kind of Breviarium where the priest finds at the same time a reduced missal, the parts of the ritual and the breviary which are the longest, the most difficult to remember by heart or the most necessary in the exercise of the ministry. The Euchologies of the Greeks are hardly otherwise composed.

The Mass of the Presanctified comes, in these books, in these Syrian Euchologia, after the ordinary mass. It is found in nine London and Paris manuscripts. It should be noted that the Wright Catalog dates all these manuscripts from about the twelfth to the thirteenth century, only one of which bears a precise date: the manuscript CCXCV, which is dated the year 1444 of the Greeks (1133 A.D.). The provenance of these manuscripts are unfortunately not indicated.

Seven of our ten manuscripts have, for the Presanctified Mass, an Anaphora which they attribute to Severus, Patriarch of Antioch; these are the ms. Paris, and those of London, which are incorporated into CCLXXXVl, CCLXXXVII, CCXCI, CCXCIV, CCXCV and CCXCVIII.

This Anaphora is followed, in CCXC, by another attributed to St. John (Chrysostom), and in the CCLXXXVII, a third attributed to St. Basil of Caesarea. Finally in the CCXCIX, the Anaphora of St. Basil is found alone.

Having not yet before our eyes the text of these Anaphoras of St. John Chrysostom and St. Basil, we do not know what relation they have with the two Greek Anaphora respectively under the names of these saints.

For that of Severus, which is, as we have just seen, the most reproduced, it is not to be confused with the Syriac Anaphora, which is now attributed to Severus, sometimes to Timothy of Alexandria. We have carefully compared them: they are totally different from each other.

Would our Anaphora be Severus’ work? We know that the latter only wrote in Greek. The Anaphora, if it is of him, is therefore only a translation. The CCXCI London manuscript categorically states that while most manuscripts simply indicate in the titles that Severus’ Anaphora is reproduced in “a new writing,” it shows us that “it has recently been translated from Greek into Syriac.” On the other hand, traces of an original Greek may not be difficult to pick up in our Anaphora. It must be noted, however, to address those whom such arguments can not satisfy, that the Syrians attribute to Severus, among many other things, the order of their liturgical offices.

Is the Anaphora of Severus known to the Syrians? The Nomocanon of Bar-Hebraeus (1226-1286), makes mention of it. Following some decisions and directions given under the names of James of Edessa and John of Tela concerning the Mass of the Presanctified, it relates, by attributing it to Severus, what one could call rubrics or rather an accurate Anaphora for this mass. There is no doubt that this precisely relates to the Anaphora we publish: it corresponds exactly to it.

The Jacobites of our day, moreover, have not yet lost the memory. The report made to the Eucharistic Congress of Jerusalem by the Syrian Bishop of Tripoli tells us, “The Jacobites, it is said, have completely abandoned the Mass of the Presanctified, although it is ordered in their liturgical books, and that Severus, the first monophysite patriarch, has made it a special liturgy.” For their part, returning to ancient traditions, Syrian Catholics have resumed the use of this Mass. However, they replaced the Anaphora of the first monophysite Patriarch with a mass (composed mainly of prayers from the liturgy of Saint James). As for the Maronites finally, it seems that they knew the Anaphora of Severus: they use it partly to adapt to the Presanctified the Anaphora of Charrar.

If we except the two Anaphoras of St. Basil and St. John Chrysostom, can we say that the churches of the Syriac rite knew no other Anaphora of this kind than that of Severus? Everything inclines us to believe it. We have just spoken of the practice of Maronites and Syrian Catholics: in the absence of a proper Anaphora, they adapt to the Presanctified one of those which serve the liturgy proper. Let us add that the authors do not mention any Anaphora of the Presanctified. It is the same with about fifteen Missals, both Maronite and Jacobite, of the National Library. Bar-Hebraeus, in his Nomocanon, does not appear to have had any other texts before him either.

This same Nomocanon allows us to explain why these kinds of Anaphora are so rare in Syria: it is because they were introduced at a remote date and they found little favor.

The reason for this scarcity is not founded, indeed, as one would be tempted to believe, on the infrequent use of the rite of the Presanctified in Syria. In the Latin Church, whose practice was belatedly adopted by the Maronites and the Catholic Syrians, it is celebrated only on Good Friday. In the Greek rite churches, even those united to Rome, it replaces the ordinary liturgy during all Lenten days except on Saturdays, Sundays and the Annunciation; these are, moreover, the prescriptions of the Quini-Sext Council (692), can. 52. As to the Syriac Church, its canonical collections are confined to the text of the Council of Laodicea (iv cent.), Canon 49: they forbid the celebration of the liturgy during Lent, except Saturdays and Sundays. but nothing is prescribed to replace it.The Greek practice was introduced there, as Renaudot and the Synod of Mont. Lebanon say, so that at a late date it would naturally have accompanied the introduction of the use of an Anaphora for the Mass of the Presanctified.

This date must be placed after the time, or at most towards the time of James of Edessa (died in 708). This author, quoted in the Nomocanon of Bar-Hebraeus, tells us, in fact, that in his time the rite of the Presanctified is practiced in the Syriac Church. The celebration is however not limited to any time of the year. Under certain conditions, it can take place three times a week; without further precision, without distinction between Lent and other liturgical periods.

According to the same author, the ritual ceremony is very simple. There is nothing there of a public office; on the contrary, it has everything of a strictly private ceremony. It is only allowed to solitary priests, and the deacon can not take any part in it, however small, and the people must not be present. We know, moreover, that the Syrian priest can only offer the holy sacrifice of the Mass, an act par excellence of public worship, attended by a deacon and in the presence of the faithful.When these two conditions are not realized, the celebration of the holy mysteries is forbidden. The consignation of the chalice, it seems, is intended to satisfy the piety of the solitary priests, and as they can not easily find a deacon or an audience to celebrate mass, they are given the opportunity to receive a sacrifice offered the day before. or even several days before. To do this, they obviously do not need an Anaphora, as James of Edessa states clearly: “To consign the chalice,” he says, “there are suggested a number of prayers, but it is in the liberty of the priest, according to the circumstances to say one or more or even to omit them altogether. In other words, to consign, no office is prescribed; that which is advised, far from being an Anaphora, are only simple prayers.

As we see, the Anaphora of Severus cannot be found in the Syriac liturgy as it is made known to us by James of Edessa. According to this author, the consigning of the chalice is a private office; to celebrate it, there is neither a mandatory and precise form, nor a limited time. This is a discipline, perhaps we can say, purely Syrian. In the Greek discipline, on the contrary, the rite of the Presanctified is a public office, celebrated in its own Anaphora and at a fixed time, during Lent. The Anaphore of Severus seems to be an attempt to introduce this discipline among Syrians. Is the London CCXCI manuscript the first to have it, as the title of the Anaphora of Severus seems to indicate? Had it already succeeded, in the time of Bar-Hebraeus, who, in his Nomocanon, reports, juxtaposed, the two disciplines without seeking, in his annotations, to explain the difference, or to reconcile them? One must, however, be careful not to exaggerate. The rarity, if not the absence, of this Anaphora in the manuscripts, except those of the twelfth century, the variants of Bar-Hebraeus’s Nomocanon concerning the Presanctified, and finally the present practice of the churches of Syria seem to indicate that the Anaphora of Severus prevailed neither everywhere nor always.

Here is the text of this Anaphora. We will follow it with a translation, illustrated by some notes borrowed from the Nomocanon of Bar-Hebraeus.

Text of the Anaphora

The consignment of the chalice of Holy Mar Severus, patriarch, according to a new writing.

First, sedro order of Entry:

Christ, our God, the true life and the immaterial food of whoever is truly hungry for you; you who have given us a spiritual drink in this fountain of delights and that source of pleasure which flows from your side, O our Savior; who have empurpled our lips with your purifying blood; and who have filled us with a healthy intoxication with the cup of blessing and gladness that you have given us, grant us strength, by your sublime grace, O friend of men, to perform the service of your awesome mysteries, with a pure and holy soul and with chaste thoughts, that with the aroma of our incense, our prayers may be acceptable to you. That our transgressions, voluntary and involuntary, (of your law), do not weary your grace, but change the mixture of this chalice laid before us into your sacred and life-giving blood, that it may cleanse us, and all your people from sin, that through it we may have forgiveness and salvation; let it preserve us from the corruption of our bodies and our souls, and for all these things we praise and worship you and your Father and your Holy Spirit.

The people: We believe in one alone.

The priest: Christ our God who entrusted to us the august mystery of your divine incarnation, sanctify this chalice of wine and water and unite it to your venerated body; that it may confer on us, and on all who receive it, the holiness of the soul, the body and the spirit, the pardon of our faults, and the forgiveness of sins, that it may cleanse us from all malice, pour out upon our consciences the dew (of forgiveness), grant us the pledge of the life to come, strength to observe your holy commandments and an apology before your terrible and terrible tribunal. Grant also that, every day of our life, might be without sins or torments, without distractions or troubles, as we have consecrated ourselves to you by sincere servitude. By your grace and the benevolence of your blessed and blessed Father and by the operation of your Holy Spirit, good, adorable, life-giving and consubstantial. Now…

The people: Amen.

The priest: Peace to you all.

The people: And to your spirit.

The priest: May the mercies of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ be with you all.

The people: And with your spirit.

The priest takes the host and signs the chalice with it, making three crosses, saying: the chalice of the actions of grace and salvation is signed by the propitiatory Host, for the pardon of our faults and the forgiveness of sins and eternal life.

The people: Amen.

The priest: Lord, God of the Holy Powers, you who hold everything and direct everything by your good will, the life of our souls, the hope of the desperate, the help of the abandoned. You who have taught us by your only Son, our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ, the prayer that we must send to you, make us worthy to dare, with a pure conscience, righteousness, love and filial trust, to invoke you, heavenly God, Father almighty and holy, and to say in our prayer.

The people: Our Father who are in heaven.

The priest: Yes, Lord, who gave us the strength and the power to tread upon snakes and scorpions and on all the forces of the Enemy, crush, without delay, his head under our feet, destroy all the wicked artifices that he multiplies against us. For you are the Almighty God and we praise you with your Father, and your Holy Spirit, good, adorable, life-giving and consubstantial with you. Now…

The people: Amen.

The priest: Peace to you all.

The people: And to your spirit.

Deacon: [Incline] our heads before the Lord.

The people: Before you. Lord God.

The priest: Receive, O Christ the King, this supplication that we make to you and listen to our requests. Send, down your mercy upon the work of your hands: turn away from our sins; look at us, O God of our salvation, and enlighten us with your merciful face and we will be saved. For your power is established forever and your kingdom will have no end. And to you are due praise, veneration and power, with your Father and your Holy Spirit, good, life-giving and consubstantial to you. Now.

The people: Amen.

The priest: Peace to you all.

The people: And to your spirit.

Priest: Grace be.

The people: And with your spirit.

Deacon: Attend with fear.

Priest: The holy things, presanctified, to the holy.

The people : One holy father.

The priest: Blessed be the name of the Lord in heaven and on earth, for ever. Amen.

The deacon: After the communion.

The priest: O adorable, very wise, infinitely blessed, only strong, God the Word, Only begotten of the Father, we who are satiated, by communion, with the delights of your holy, immortal and life-giving mysteries, we send our praises, venerations and adorations to you and to your Father without blemish and to your Holy Spirit. Now.

The people : Amen.

The priest: Peace to you all.

The people: And to your spirit.

The deacon: [Incline] our heads before the Lord.

The people: Before you. Lord our God.

The priest: The whole human race can not be enough, O Lord Jesus Christ, to give thanks to your ineffable goodness, for having us given your sacred body and your purifying blood. So, we beg you to grant us to commune there always, our heart being pure and holy, and our soul and our spirit. Bless your people and keep your inheritance, so that, constantly and always, we praise you, you who are alone our true God and God the Father who begot you and your Holy Spirit, good, life-giving and consubstantial to you. Now.

The people: Amen.

The deacon: Bless, Lord.

The priest: Grant to bless us, to keep us, to sanctify us to protect and show us the way of life and salvation. And our mouth, will bring forth the praise of your sovereignty, O our Lord and Savior of our souls, forever.

End of the consignment of the chalice.

[Originally translated into French by Michel Rajji in 1919]